Fitbit recently released data showing a global decrease in physical activity levels among users of its activity trackers compared to the same time last year.

As we navigate the coronavirus pandemic, this is not altogether surprising. We’re getting less of the “incidental exercise” we normally get from going about our day-to-day activities, and many of our routine exercise options have been curtailed.

While we don’t know for sure how long our lifestyles will be affected in this way, we do know periods of reduced physical activity can affect our health.

Older people and those with chronic conditions are particularly at risk.

Read more: How to stay fit and active at home during the coronavirus self-isolation

Cardiorespiratory fitness

To understand why the consequences of inactivity could be worse for some people, it’s first important to understand the concept of cardiorespiratory fitness.

Cardiorespiratory fitness provides an indication of our overall health. It tells us how effectively different systems in our body are working together, for example how the lungs and heart transport oxygen to the muscles during activity.

The amount of physical activity we do influences our cardiorespiratory fitness, along with our age. Cardiorespiratory fitness generally peaks in our 20s and then steadily declines as we get older. If we’re inactive, our cardiorespiratory fitness will decline more quickly.

As we get older, our cardiorespiratory fitness declines.Shutterstock

As we get older, our cardiorespiratory fitness declines.ShutterstockOne study looked at five young healthy men who were confined to bed rest for three weeks. On average, their cardiorespiratory fitness decreased 27% over this relatively short period.

These same men were tested 30 years later. Notably, three decades of normal ageing had less effect on cardiorespiratory fitness (11% reduction) than three weeks of bed rest.

This study demonstrates even relatively short periods of inactivity can rapidly age the cardiorespiratory system.

Read more: 5 ways nutrition could help your immune system fight off the coronavirus

But the news isn’t all bad. Resuming physical activity after periods of inactivity can restore cardiorespiratory fitness, while being physically active can slow the decline in cardiorespiratory fitness associated with normal ageing.

Staying active at home

Generally, we know older adults and people with chronic health conditions (such as heart disease or type 2 diabetes) have lower cardiorespiratory fitness compared to younger active adults.

This can heighten the risk of health issues like another heart disease event or stroke, and admission to hospital.

While many older people and those with chronic health conditions have been encouraged to stay home during the COVID-19 pandemic, it’s still possible for this group to remain physically active. Here are some tips:

set a regular time to exercise each day, such as when you wake up or before having lunch, so it becomes routine

aim to accumulate 30 minutes of exercise on most if not all days. This doesn’t have to all be done at once but could be spread across the day (for example, in three ten-minute sessions)

use your phone to track your activity. See how many steps you do in a “typical” day during social distancing, then try to increase that number by 100 steps per day. You should aim for at least 5,000 steps a day

take any opportunity to get in some activity throughout the day. Take the stairs if you can, or walk around the house while talking on the phone

try to minimise prolonged periods of sedentary time by getting up and moving at least every 30 minutes, for example during the TV ad breaks

incorporate additional activity into your day through housework and gardening.

Read more: Why are older people more at risk of coronavirus?

A sample home exercise program

First, put on appropriate footwear (runners) to minimise any potential knee, ankle or foot injuries. Also ensure you have a water bottle close by to stay hydrated. If you have any knee soreness or other knee issues, consider wearing a knee compression sleeve or knee brace.

It may be useful to have a chair or bench nearby in case you run into any balance issues during the exercises.

Start with five minutes of gentle warm up such as a leisurely walk around the back garden or walking up and down the hallway or stairs

then pick up the pace a little for another ten minutes of cardio – such as brisk walking, or skipping or marching on the spot if space is limited. You should work at an intensity that makes you huff and puff, but at which you could still hold a short conversation with someone next to you

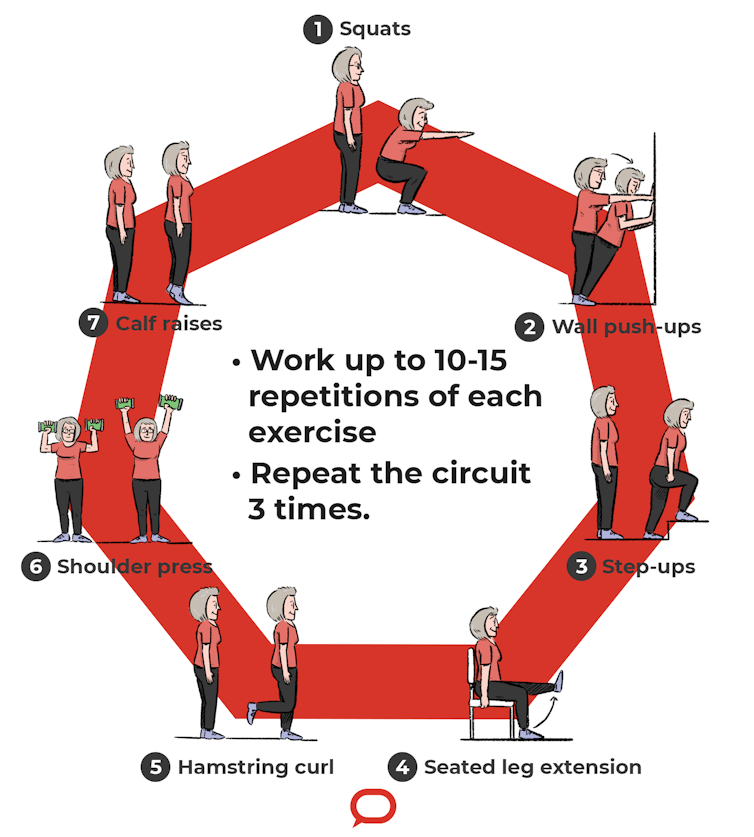

The Conversation, CC BY-ND

The Conversation, CC BY-NDnext, complete a circuit program. This means doing one set of six to eight exercises (such as squats, push ups, step ups, bicep curls or calf raises) and then repeating the circuit three times

- these exercises can be done mainly using your own body weight, or for some exercises you can use dumbbells or substitutes such as bottles of water or cans of soup

- start with as many repetitions as you can manage and work up to 10-15 repetitions of each exercise

- perform each exercise at a controlled tempo (for example, take two seconds to squat down and two seconds to stand up again)

finish with five minutes of gentle cool down similar to your warm up.

Read more: Every cancer patient should be prescribed exercise medicine

If you have diabetes, check your blood sugar levels before, during and after you exercise, and avoid injecting insulin into exercising limbs.

If you have a heart condition, it’s important to warm up and cool down properly and take adequate rests (about 45 seconds) after you complete the total repetitions for each exercise.

For people with cancer, consider your current health status before you start exercising, as cancers and associated treatments may affect your ability to perform some activities.

Rachel Climie receives funding from the Heart Foundation.

Erin Howden receives funding from the Heart Foundation.

Authors: Rachel Climie, Exercise Physiologist and Research Fellow, Baker Heart and Diabetes Institute

| < Prev | Next > |

|---|