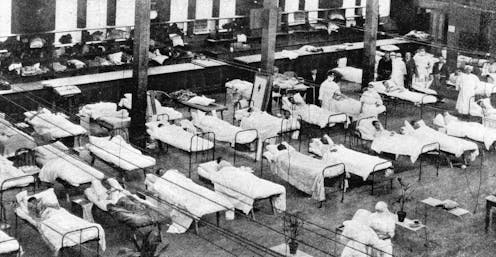

Makeshift hospital beds at the Royal Exhibition Building in Melbourne during the influenza pandemic of 1919.Museum Victoria

Makeshift hospital beds at the Royal Exhibition Building in Melbourne during the influenza pandemic of 1919.Museum VictoriaPublic health messages about COVID-19 have been inconsistent and changed rapidly. Many have called for a unified source of expertise to guide responses to the crisis.

However, with the federal, state and local governments, as well as international bodies, offering different advice, it is no simple task to “listen to the experts”.

In uncertain situations such as the COVID-19 pandemic, biomedical and public health experts contribute facts and their own judgements about risk to our collective thinking and decision making.

The public also have important contributions to make. In response to the spread of coronavirus, community groups are setting out to care for elderly neighbours. People are remembering the importance of nurturing community connections and developing an understanding of the structural burdens placed on women in times of crisis.

Alongside traditional kinds of expertise, this kind of “real time” expertise and leadership at the local scale will be invaluable in coming weeks and months.

Read more: Uncertain? Many questions but no clear answers? Welcome to the mind of a scientist

Expertise is political

Expert judgements don’t exist in a vacuum. They arise from specific social and political contexts. To understand them, we need to acknowledge the tacit assumptions embedded within expert knowledge claims, especially assumptions concerning how publics respond to expert advice.

In recent weeks there has been much debate about the federal governments’s decision to keep schools open, which has only been made more uncertain by disagreements between experts over the role of schools in the transmission of COVID-19.

Similarly, in the Ruby Princess “debacle”, different governments and agencies have attempted to blame each other and drawn on expert knowledge claims to justify their actions.

These examples demonstrate how expertise is entangled with questions of political judgement and anticipated societal responses.

For publics, it can be hard to distinguish between health experts working for the government and those criticising the government. Experts tend to look alike, sound alike, and “advise” alike, leaving publics to navigate the cacophony.

In this situation, deciding which experts to listen to can become a nearly impossible task. Little wonder many people have been slow to change their behaviour.

Understanding public responses

As recently as two months ago, during Australia’s catastrophic bushfire season, publics were seen as resourceful and resilient. That image has quickly been replaced by a characterisation as vulnerable, easily spooked, and panicking in the face of uncertainty.

However, we can understand buying food, cleaning products, face masks, toiletries, and medication for asthma and fevers as reasonable responses to questions that experts themselves are trying to address in real time. For example, medical anthropologist Christos Lynteris has argued that face mask buying sprees are a reminder we should think of epidemics “not simply as biological events but also as social processes”.

Read more: Stocking up to prepare for a crisis isn't 'panic buying'. It's actually a pretty rational choice

Science studies scholar Brian Wynne has said the idea of public trust in expertise is too simple. The relationship between publics and experts is complex and ambivalent, he argues, and qualified by “the experience of dependency, possible alienation, and lack of agency”.

Public responses to COVID-19 are not as simple as a mass panic, but they signal something more worrying. The public lacks confidence in public health infrastructure and its ability to contain the virus. “Toilet paper panic” is the response of a population for whom expert advice is one factor among many that affect their feelings of security and wellbeing.

For experts seeking to contribute to public decision making, researchers have empirically demonstrated the productive value of collaborative approaches. For example, sociologist Steven Epstein has documented how collaborations between researchers and broader “lay experts” during the AIDS/HIV epidemic in the 1990s played a key role in the public health response to the disease.

Engaging public expertise, even in times of crisis

But how do we achieve meaningful engagement between publics and experts? Broadening our understanding of expertise would be a start.

Expertise might include the outpouring of creative expression prompted by COVID-19, or the surge in creation of mutual support groups.

Likewise, efforts to translate health warnings are essential for engaging vulnerable communities. These networks of varied expertise are likely to prove invaluable when existing governance is over-stretched or breaks down.

Diverse, diffuse, and local initiatives are likely to continue during periods of chaos, with the added advantage of feeding further expertise from the ground back into the knowledge system.

The need for a diversity of expertise is already being recognised in responses to COVID-19. The WHO recommends risk communication strategies should “promote a two-way dialogue with communities, the public and other stakeholders”.

The ABC’s Coronacast podcast is one such two-way channel that responds to public concerns and questions. Scientists are also seeking volunteer researchers in the effort to address COVID-19, and many viral social media threads sharing notes on patients’ experience of triage and care have been important sources of information for healthcare workers.

Attending to the dynamism and diversity of expertise does not diminish its invaluable roles in society.

Understanding that the crisis of COVID-19 is also a social one should raise questions of how our traditional reliance on expert advice relegates local expertise to the sidelines.

It is critical that we recognise how local expertise is filling the gaps in government policies and expert advice, and is likely to continue to do so in crises such as the recent bushfires and the COVID-19 pandemic.

We have an opportunity to appreciate that community responses are characterised by their own expertise. We ought also to listen to those experts.

Matthew Kearnes receives funding from the Australian Research Council.

Brian Robert Cook receives funding from The Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research

Declan Kuch receives funding from the Australian Renewable Energy Agency and Australian Research Council.

Joan Leach receives funding from The Australian Research Council.

Niamh Stephenson receives funding from the Australian Research Council.

Rachel A. Ankeny receives funding from the Australian Research Council.

Sujatha Raman is a member of the CSIRO-ANU joint-funded research collaboration in responsible innovation. She has received funding in the past from the UK Leverhulme Trust and UK research councils (ESRC, BBSRC, EPSRC, NERC).

Authors: Matthew Kearnes, Professor, Environment & Society, School of Humanities and Languages, UNSW

| < Prev | Next > |

|---|