The extreme volatility and losses seen in stock markets in recent weeks has seen calls for financial markets to be closed and short selling restricted.

But shutting them down would be a mistake.

Amid the volatility, financial market prices convey much needed information.

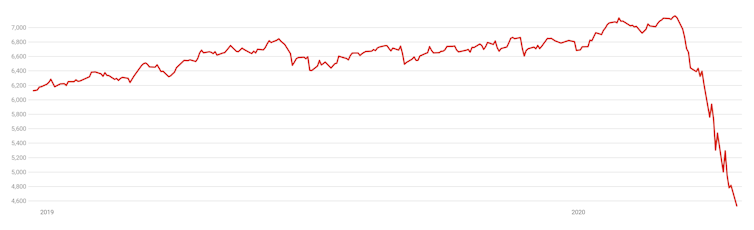

S&P/ASX 200 share index over the past year

Source: Yahoo Finance

Source: Yahoo FinanceIn an early morning meeting at the White House the day after the 1987 stock market crash, then US Treasury Secretary Jim Baker floated the idea of closing the stock market.

The Chair of President Reagan’s Council of Economic Advisers, the Chicago-trained monetarist Beryl Sprinkel, was having none of it.

According to several second and third-hand accounts, when his opinion was sought, Sprinkel said “we will close the markets when monkeys come flying out of my ass.”

When Reagan asked Fed Chair Alan Greenspan for his opinion, Greenspan declared, “I go with the monkeys”.

The US stock market stayed open that day and rallied late in the afternoon, injecting a note of much-needed confidence.

Prices tell us truths

The Fed’s operations to maintain liquidity (the ability to buy and sell) remain a textbook case of how to respond to severe financial market stress.

The US economy was spared recession on that occasion.

Today’s situation is different in important respects. Policymakers are choosing to shut down the economy, and financial markets are pricing shares accordingly. Bond markets have been shaken as investors sell bonds to raise cash and prepare for governments to issue a flood of new bonds.

Read more: More than a rate cut: behind the Reserve Bank's three point plan

The US dollar has rallied as the world scrambles for US dollars, sending exchange rates against the US dollar dramatically lower.

As my previous research shows, the US dollar often climbs when the economic outlook is most dire, explaining why the Australian dollar is at its lowest in nearly two decades.

US cents per Australian dollar

Source: Reserve Bank of Australia

Source: Reserve Bank of AustraliaAmid such extreme volatility, it would be tempting to close financial markets, in particular, stock exchanges.

There is no reason to close markets for reasons of public health. Financial markets are now traded almost entirely electronically. The US has been forced to close its trading floors in New York and Chicago, but these trading floors were already legacies of an earlier era, largely ornamental adornments to digital trading.

Stock markets have their own circuit breakers that kick in during extreme volatility, but to do more than that would be to deprive traders and policymakers of the insights they offer.

Price movements function as alerts. It is noteworthy that financial markets sold off days before the World Health Organisation finally declared a pandemic.

Read more: This coronavirus share market crash is unlike those that have gone before it

They can also inform policymakers about what to do. When share markets begin a sustained recovery, it will be a sign the worst of the pandemic might be behind us.

We need prices for financial products in the same way we need prices for goods and services. Without them, decision-making becomes difficult, if not impossible.

Preventing investors from selling stocks to raise cash (which is what a stock market shutdown would do) could cause severe hardship.

With share market prices falling sharply, it’s tempting to think closing them will stem the losses, but it could trigger even more painful adjustments elsewhere.

Even short sellers have a place

Other countries have imposed bans on short selling, which is the sale of a share the seller does not yet own.

Short sellers profit by buying back shares at a lower price after they have sold them. They do it by borrowing rather than owning stocks. Their actions help the owners of stocks who want to protect their financial positions from further declines in price.

If owners can’t protect themselves in this way, they can be forced to liquidate shares, making the downturn even worse.

Read more: Coronavirus market chaos: if central bankers fail to shore up confidence, then what?

The global financial crisis gave us a wealth of experience with bans on short-selling, including in Australia. The evidence from that experience overwhelmingly suggests short-selling bans were counter-productive.

Keeping markets open will be a painful experience for many, but closing them is the equivalent of shooting the messenger.

Eventually, they will signal better times ahead and give business the confidence to move forward with the recovery.

Stephen Kirchner is also a senior fellow at The Fraser Institute.

Authors: Stephen Kirchner, Program Director, Trade and Investment, United States Studies Centre, University of Sydney

| < Prev | Next > |

|---|