Susan Arthure, Author provided

Susan Arthure, Author providedArchaeological research has uncovered the remains of a 19th-century Irish community beneath an otherwise ordinary paddock in rural South Australia. Fitting the clustered form of settlement known as a “clachan”, it’s the first to be identified in Australia. Even more remarkably, this community thrived many years after this traditional way of living died out in Ireland.

Kapunda is today a town of about 3,000 people located 77km north of Adelaide.Google Maps

Kapunda is today a town of about 3,000 people located 77km north of Adelaide.Google MapsThe story of this discovery began in November 2012 when I walked for the first time on Baker’s Flat near Kapunda, about an hour’s drive north of Adelaide. I was an Irish-Australian archaeologist in search of an Irish colonial settlement.

In 1842, the discovery of copper at Kapunda led to the development of Australia’s first successful metal mine. The Irish arrived in 1854, seeking work as mine workers. They settled on an unused section of land close to the mine known as Baker’s Flat.

Read more: Why archaeology is so much more than just digging

The Irish of Baker’s Flat

The histories are not kind to the Irish of Baker’s Flat. A 1929 collection of Kapunda stories established a narrative about the settlement as haphazard and chaotic, full of squalid hovels and unrestrained animals, and which essentially operated as a closed Irish community set apart from the rest of the town. Along with newspaper accounts of fights, public drunkenness and land disputes, the scene was set for these Irish to be perceived in stereotypical fashion as dirty, drunk, rebellious and lawless.

Years later, in the 1950s, the remains of any houses were demolished so the land could be farmed. Baker’s Flat was effectively erased from the landscape. The Irish were forgotten.

When I began researching the archives, trawling through the records of court cases and land disputes, I was really just trying to understand that community better.

The Irish had occupied Baker’s Flat from 1854 until at least the 1920s. At its peak in the 1860s and 1870s, 500 people were living there. Surely they couldn’t all be drunk and rebellious, or as one-dimensional as the dominant narrative implied.

Read more: Aussie slang is as diverse as Australia itself

Following the clachan trail

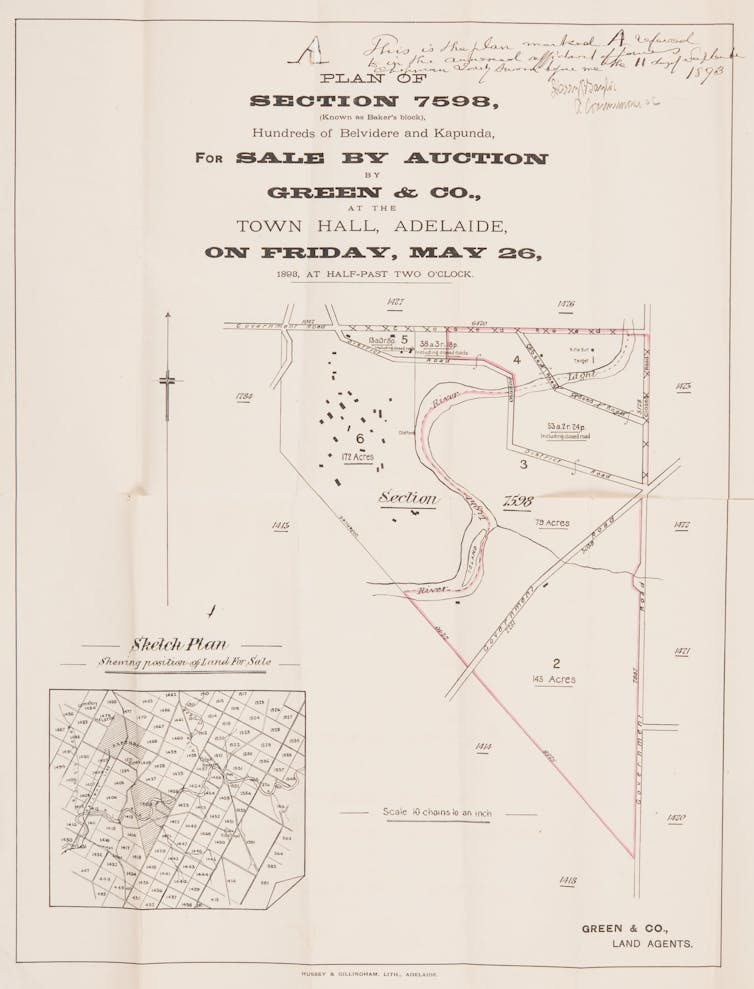

I was looking for more depth and balance, but what I found turned out to be even more interesting. A surveyor’s plan from 1893 is the only historic map of the site. It shows a cluster of buildings in the north-west quadrant.

Survey plan of Baker’s Flat, 1893, showing houses clustered together.State Records SA GRG 36/54/1892/47. Author provided

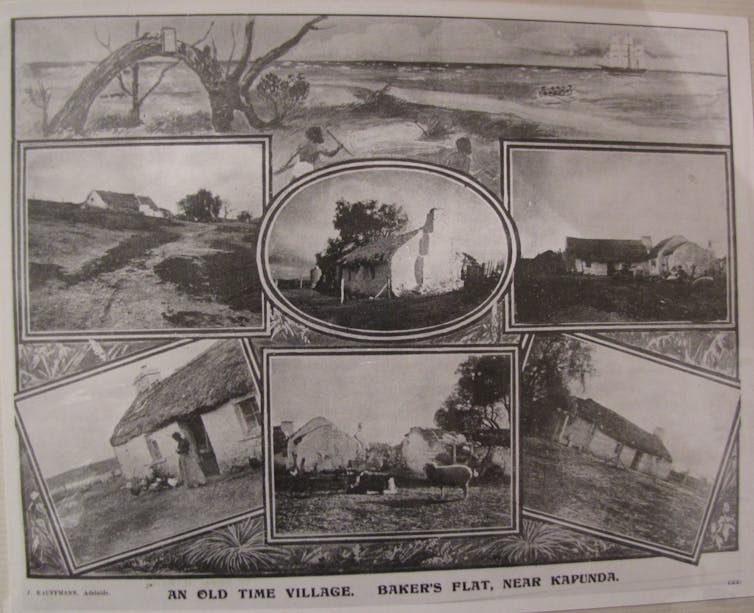

Survey plan of Baker’s Flat, 1893, showing houses clustered together.State Records SA GRG 36/54/1892/47. Author providedA series of photographs from 1906 depicts Irish-style cottages nestled into the landscape.

Photos by John Kauffmann depicting Baker’s Flat houses in 1906.Susan Arthure, from a copy held at Kapunda Historical Society Museum

Photos by John Kauffmann depicting Baker’s Flat houses in 1906.Susan Arthure, from a copy held at Kapunda Historical Society MuseumAffidavits from a court case disputing ownership and control of the land describe shared decisions, collective action and communal animal management. These facts hinted that this community might have operated as a clachan.

This traditional Irish way of living was characterised by clusters of farm dwellings and outbuildings built in the Irish style. In a clachan, the inhabitants managed the farming land communally. Unlike a classic village, clachans did not have services like shops or pubs.

Until the mid-19th century, clachans were widespread in Ireland. They died out, however, in the social upheaval following the Great Famine of 1845–1850. My research at this point indicated that, while the clachan was vanishing in Ireland, a vibrant one was flourishing in the heart of South Australia. Significantly, the only other clachan outside of Ireland to be hinted at so far is a cluster of houses built by 19th-century Irish migrants on Beaver Island, Lake Michigan.

Bringing in the archaeology

The next step was to test my theory using archaeological methods. First was a surface survey in 2013. Teams of archaeology students walked along a set route, observing and recording what they could see on the surface.

The first fieldwork on the site, a survey to determine what is visible on the surface.Susan Arthure

The first fieldwork on the site, a survey to determine what is visible on the surface.Susan ArthureThis survey identified the remains of 13 buildings (now just small heaps of rubble) and scattered broken glass and ceramics, mainly in the north-west quadrant.

Based on these findings, we carried out a geophysical survey in 2016. Using ground-penetrating radar and a magnetic gradiometer, we found several large sub-surface features.

Kelsey Lowe uses a magnetic gradiometer at the site of the clachan.Susan Arthure

Kelsey Lowe uses a magnetic gradiometer at the site of the clachan.Susan ArthureThese were clustered together and fit the pattern of rectangular structures about 10m long and 5m wide. There were also indications of paths and enclosures.

We tested these findings by excavation over two summer field seasons in 2016 and 2017. The excavations uncovered the walls of a long rectangular house, dug into the bedrock. It was one room deep, shaped like a traditional Irish dwelling, and matched the design of the photographed houses from 1906.

There was a cobbled path to the east. A small rubbish dump contained many 19th-century glass and ceramic fragments and butchered bones.

Read more: Googling the past: how I uncovered prehistoric remains from my office

A newly excavated ceramic fragment.Susan Arthure

A newly excavated ceramic fragment.Susan ArthureHere lies a clachan

When all the evidence is combined, it confirms the presence of a clachan, the first to be identified in Australia. Analysis of the glass, ceramic and bone artefacts is ongoing but indicates so far that the Irish were generally drinking, eating and using the same things as other members of the broader colonial Australian community.

What is different here is the way they chose to live, building houses in the Irish tradition, living close together and making decisions jointly.

We do not know if the Baker’s Flat Irish deliberately set out to establish a clachan in a small corner of South Australia. It was such a common style of living at the time they left Ireland it may well be they just continued doing what they had always done and that it emerged organically. But they left enough behind to build a picture that challenges the stereotypes.

The archaeology is revealing that it wasn’t all chaos and lawlessness at Baker’s Flat. There was order. And this order took the particular form of the clachan.

Susan Arthure with some artefacts excavated from Baker’s Flat that have been analysed and reconstructed.Flinders University. Author provided

Susan Arthure with some artefacts excavated from Baker’s Flat that have been analysed and reconstructed.Flinders University. Author providedAs well as looking at the ancient past, archaeology is also about the recent past and what might lie beneath an unassuming paddock. It focuses on people and the things they discard or leave behind. For me, it’s about ordinary people, whose stories get forgotten as time goes by, but who leave traces in the landscape and the archives for archaeologists to uncover.

Susan Arthure receives funding from an Australian Government Research Training Program Scholarship and Flinders University to support her research.

Authors: Susan Arthure, PhD Candidate, Archaeology, Flinders University, Flinders University

| < Prev | Next > |

|---|