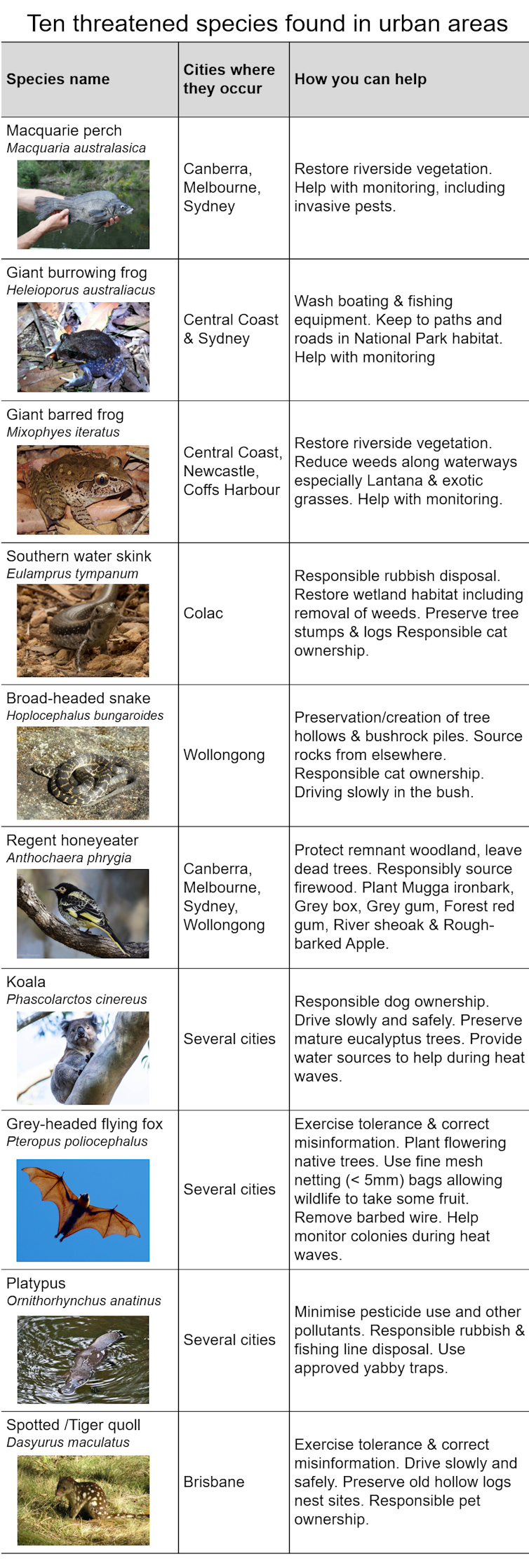

People living in cities far from the unprecedented bushfires this summer may feel they can do little more to help beyond donating to organisations that support affected wildlife. But this is not necessarily the case: ten of the 113 top-priority threatened animal species most affected by the fires have populations in and around Australian cities and towns. Conserving these populations is now even more critical for the survival of these species.

Here we provide various practical tips on things people can do in their own backyards and neighbourhoods to help some of the species hit hard by the fires.

Read more: The 39 endangered species in Melbourne, Sydney, Adelaide and other Australian cities

Wildlife may arrive in your neighbourhood in search of resources lost to fire or drought in their ranges. Cities can become ecological traps, as they draw animals towards sub-optimal habitats or even death from threats such as cats and cars. But by providing the right resources, removing threats and connecting your backyard to surrounding habitat, you can turn your property into a refuge, not a trap.

Images from Flickr by: Jarod Lyon (Macquarie perch), Doug Beckers (Giant burrowing frog), eyeweed (Giant barred frog), Catching The Eye (Southern water skink), Alan Couch (Broad-headed snake), Brian McCauley (Regent honeyeater), Ron Knight (Koala), Duncan PJ (Grey-headed flying fox), Tony Morris (Platypus) and Pierre Pouliquin (Tiger quoll).Author provided

Images from Flickr by: Jarod Lyon (Macquarie perch), Doug Beckers (Giant burrowing frog), eyeweed (Giant barred frog), Catching The Eye (Southern water skink), Alan Couch (Broad-headed snake), Brian McCauley (Regent honeyeater), Ron Knight (Koala), Duncan PJ (Grey-headed flying fox), Tony Morris (Platypus) and Pierre Pouliquin (Tiger quoll).Author providedThe fires killed an estimated 1 billion animals and Australia’s threatened species list is likely to expand dramatically. As is often the case, the impacts on invertebrates have been largely ignored so far.

Read more: Conservation scientists are grieving after the bushfires -- but we must not give up

Thinking outside the animal box

Despite the focus on animals, it is plants, making up 1,336 of the 1,790 species listed as threatened, that have been hit hardest. Early estimates are that the fires had severe impacts on 272 threatened plant species. Of these, 100 are thought to have had more than half of their remaining range burnt.

The impacts on individual plant species is profoundly saddening, but the impacts on whole ecosystems can be even more catastrophic. Repeated fires in quick succession in fire-sensitive ecosystems, such as alpine-ash forests, can lead to loss of the keystone tree species. These trees are unable to mature and set seed in less than 20 years.

Losing the dominant trees leads to radical changes that drive many other species to extinction in an extinction cascade. Other badly impacted ecosystems include relics of ancient rainforests, which might not survive the deadly combination of drought and fire.

Read more: A season in hell: bushfires push at least 20 threatened species closer to extinction

It is difficult to know how best to “rescue” threatened plants, particularly when we know little about them. Seed banks and propagation of plants in home gardens can be a last resort for some species.

You can help by growing plants that are indigenous to your local area. Look for an indigenous nursery near you that can provide advice on their care. Advocate for mainstream nurseries, your council and schools to make indigenous plants available to buy and be grown in public areas.

Example of alpine ash (Eucalyptus delegatensis) forest in Victoria.Holly Kirk

Example of alpine ash (Eucalyptus delegatensis) forest in Victoria.Holly KirkProviding for urban wildlife

Planting native species in your backyard is also the best way to provide food for visiting wildlife. Many species feed on flower nectar, or on the insects the vegetation attracts. Putting out dishes of fruit or bird feeders can be useful for some species, but the best way to provide extra food for all is by gardening.

Plants also provide shelter and nest sites, so think twice about removing vegetation, leaf litter and dead wood. Fire risk can be managed by selecting species that are fire-suppressing.

Urban gardens also provide water for many thirsty creatures. If you put out a container of water, place rocks and branches inside so small critters can escape if they fall in.

Read more: You can leave water out for wildlife without attracting mosquitoes, if you take a few precautions

Backyard ponds can provide useful habitat for some frog species, particularly if you live near a stream or wetland. Please don’t add goldfish!

The best frog ponds have plants at the edges and emerging from the water, providing calling sites for males and shelter for all. Insecticides and herbicides harm frogs as well as insects and plants, so it’s best not to use these in your garden.

Piles of rocks in the garden form important shelters for lizards and small mammals.

Reducing threats

It’s important to consider threats too. Cats kill native wildlife in huge numbers. Keep your pet inside or in a purpose-built “catio”.

Read more:For whom the bell tolls: cats kill more than a million Australian birds every day

Read more:A hidden toll: Australia’s cats kill almost 650 million reptiles a year

When driving, think about killing your speed rather than wildlife – especially while populations are moving out of fire-affected areas in search of food. Slowing down can greatly reduce animal strikes.

With the loss of huge areas of forest, species like grey-headed flying foxes will need to supplement their diet with fruit from our backyards. Unfortunately, they risk being entangled in tree netting. If you have fruit trees, consider sharing with wildlife by removing nets, or using fine mesh bags to cover only select bunches or branches.

Read more: Not in my backyard? How to live alongside flying-foxes in urban Australia

Living with the new visitors

People have different levels of knowledge about our native wildlife, and some will be more affected by new wildlife visitors than others. Some of these critters are small and quiet. Others are more conspicuous and may even be considered a nuisance.

Try to discuss what you are seeing and experiencing with your neighbours. When you can, provide information that might ease their concerns, but also be sympathetic if noisy or smelly residents move in. It is important to tolerate and co-exist with wildlife, by acknowledging they might not conform to neighbourly conventions.

Given the unprecedented extent and intensity of these fires, it is difficult for scientists to predict how wildlife will respond and what might show up where. This is especially the case for species, like the regent honeyeater, that migrate in response to changing resources. New data will be invaluable in helping us understand and plan for future events like these.

If you do see an animal that seems unusual, you can report it through citizen-science schemes such as iNaturalist. If an animal is injured or in distress it’s best to contact a wildlife rescue organisation such as Wildlife Victoria or WIRES (NSW).

Read more: How you can help – not harm – wild animals recovering from bushfires

Our wildlife is under pressure now, but we can help many populations by ensuring safer cities for the species that share them with us.

Resources

How to help birds after the fires

Other threatened species in cities

Find your local native nursery

Learn about platypus-safe yabby nets

Holly Kirk receives funding from National Environment Science Program through the Clean Air and Urban Landscapes Hub.

Brendan Wintle receives research funding from the Australian Government's National Environmental Science Program, the Victorian Government, and the Australian Research Council.

Casey Visintin receives funding from The National Environment Science Program through the Threatened Species Recovery Hub. He is a member of both Wildlife Victoria and the Australasian Bat Society.

Freya Thomas receives funding from the Australian Research Council Linkage Program (LP160100324). She is a council member for Wollangarra Outdoor Education Centre.

Georgia Garrard receives funding from the Australian Research Council through the Linkage and Discovery Project Schemes, and the National Environmental Science Program through the Threatened Species Recovery Hub. She is a member of the Victorian Government Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning's Scientific Reference Panel.

Kirsten Parris receives funding from the Australian Research Council and the Commonwealth Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment. She leads the National Environmental Science Program's Research Hub for Clean Air and Urban Landscapes (CAUL), co-convenes the Science Communication Research Chapter of the Ecological Society of Australia, and is an Honorary Associate of the Royal Botanic Gardens Victoria.

Kylie Soanes receives funding from The National Environment Science Program through the Threatened Species Recovery Hub and the Clean Air and Urban Landscapes Hub. She is a board member of the Greater Melbourne Chapter of the Society for Conservation Biology.

Pia Lentini receives funding from the Australian Research Council Linkage scheme (LP160100439). She is a Board Member of Wildlife Victoria and sits on the Executive of the Australasian Bat Society.

Sarah Bekessy receives funding from The National Environment Science Program through the Threatened Species Recovery Hub and the Clean Air and Urban Landscapes Hub, the Australian Research Council Linkage Program (LP160100324) and the H2020 Urban GreenUp project. She is a Board member of Bush Heritage Australia and a member of WWF Eminent Scientist Group.

Authors: Holly Kirk, Postdoctoral Fellow, Interdisciplinary Conservation Science Research Group (ICON Science), RMIT University

| < Prev | Next > |

|---|