National Map

National MapEditor’s note: These before-and-after-images from several sources –NASA’s Worldview application, National Map by Geoscience Australia and Digital Earth Australia – show how the Australian landscape has responded to huge rainfall on the east coast over the last month. We asked academic experts to reflect on the story they tell:

Warragamba Dam, Sydney

Stuart Khan, water systems researcher and professor of civil and environmental engineering.

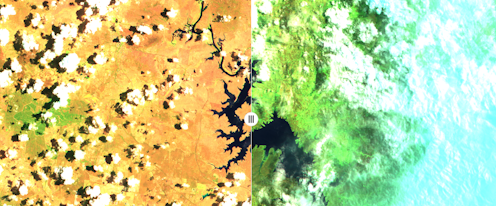

This map from Digital Earth Australia shows a significant increase in water stored in Lake Burragorang. Lake Burragorang is the name of water body maintained behind the Warragamba Dam wall and the images show mainly the southern source to the lake, which is the Wollondilly River. A short section of the Coxs River source is also visible at the top of the images.

The Warragamba catchment received around 240mm of rain during the second week of February, which produced around 1,000 gigalitres (GL) of runoff to the lake. This took the water storage in the lake from 42% of capacity to more than 80%.

Unlike a typical swimming pool, the lake does not generally have vertical walls. Instead, the river valley runs deeper in the centre and more shallow around the edges. As water storage volumes increase, so does the surface area of water, which is the key feature visible in the images.

Leading up to this intense rainfall event, many smaller events occurred, but failed to produce any significant runoff. The catchment was just too dry. Dry soils act like a sponge and soak up rainfall, rather than allowing it to run off to produce flows in waterways.

The catchment is now in a much wetter state and we can expect to see smaller rainfall events effectively produce further runoff. So water storage levels should be maintained, at least in the short term.

However in the longer term, extended periods of low rainfall and warm temperatures will make this catchment drier.

In the absence of further very intense rainfall events, Sydney will lapse back into drought and diminishing water storages.

This pattern of decreasing storage, broken only by very intense rainfall, can be observed in Sydney’s water storage history.

It is a pattern likely to be exacerbated further in future.

Wivenhoe Dam, Brisbane

@media only screen and (max-width: 450px) { iframe.juxtapose { height: 320px; width: 100%; } } @media only screen and (min-width: 451px) and (max-width: 1460px) { iframe.juxtapose { height: 400px; width: 100%; } }Stuart Khan, water systems researcher and professor of civil and environmental engineering.

Lake Wivenhoe is the body of water maintained behind Wivenhoe Dam wall in southeast Queensland. It is the main water storage for Brisbane as well as much of surrounding southeast Queensland.

This image from National Map shows a visible change in colour from brown to green in the region around the lake. It is quite startling.

This is especially the case to the west of the lake, in mountain range areas such as Toowoomba, Warwick and Stanthorpe. Many of these areas were in very severe drought in January. Stanthorpe officially ran out of water. The February rain has begun to fill many important water storage areas and completely transformed the landscape.

Unfortunately, this part of Australia is highly prone to drought and we can expect to see this pattern recur over coming decades.

Much climate science research indicates more extreme weather events in future. That means more extreme high temperatures, more intense droughts and more severe wet weather.

There are many challenges ahead for Australian water managers as they seek to overcome the inevitable booms and busts of future water availability.

Read more: Bushfires threaten drinking water safety. The consequences could last for decades

Australia-wide

@media only screen and (max-width: 450px) { iframe.juxtapose { height: 320px; width: 100%; } } @media only screen and (min-width: 451px) and (max-width: 1460px) { iframe.juxtapose { height: 400px; width: 100%; } }Grant Williamson, Research Fellow in Environmental Science, University of Tasmania

It’s clear from this map above, from NASA Worldview, the monsoon has finally arrived in northern Australia and there’s been quite a lot of rain.

On the whole, you can see how rapidly the Australian environment can respond to significant rainfall events.

It’s important to remember that most of that greening up will be the growth of grasses, which respond more rapidly after rain.

The forests that burned will not be responding that quickly. The recovery process will be ongoing and within six months to a year you’d expect to see significant regrowth in the eucalyptus forests.

Other more fire-sensitive vegetation, like rainforests, may not exhibit the same sort of recovery.

Grant Williamson, Research Fellow in Environmental Science, University of Tasmania

This slider from National Map shows both fire impact, and greening up after rain.

On the left – an area west of Cooma on December 24 – you can see the yellow treeless areas, indicating the extent of the drought, and the dark green forest vegetation. This image also shows quite a lot of smoke, as you’d expect.

On the right – the area on February 22 – a lot of those yellow areas are now significantly greener after the rain. However, some of those dark green forest areas are now brown or red, where they have been burnt.

It’s clear there is a long road ahead for recovery of these forests that were so badly burned in the recent fires but they will start resprouting in the coming months.

Grant Williamson is a Tasmania-based researcher with the NSW Bushfire Risk Management Research Hub.

Authors: Sunanda Creagh, Head of Digital Storytelling

| < Prev | Next > |

|---|