Shutterstock

ShutterstockThe alarming rate of carbon dioxide flowing into our atmosphere is affecting plant life in interesting ways – but perhaps not in the way you’d expect.

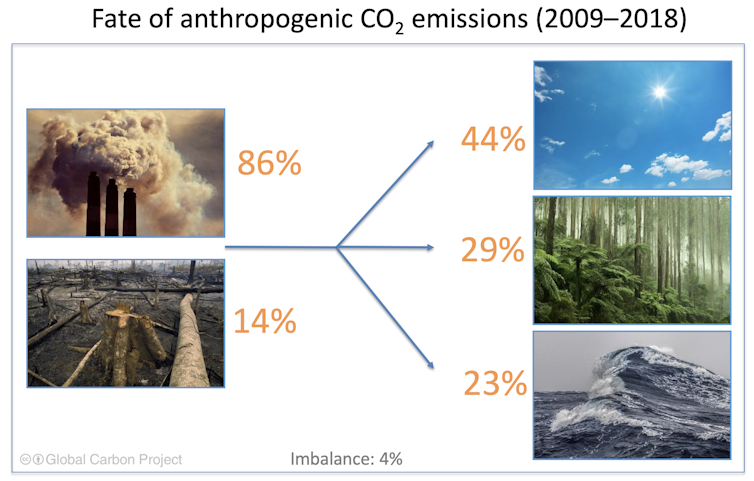

Despite large losses of vegetation to land clearing, drought and wildfires, carbon dioxide is absorbed and stored in vegetation and soils at a growing rate.

This is called the “land carbon sink”, a term describing how vegetation and soils around the world absorb more carbon dioxide from photosynthesis than they release. And over the past 50 years, the sink (the difference between uptake and release of carbon dioxide by those plants) has been increasing, absorbing at least a quarter of human emissions in an average year.

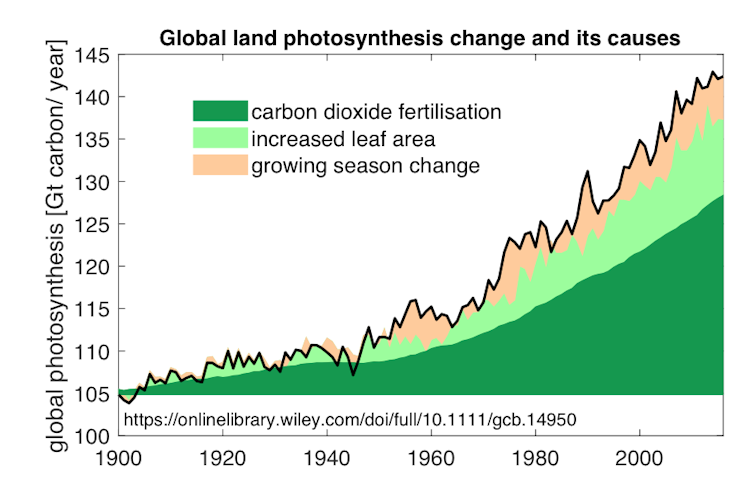

The sink is getting larger because of a rapid increase in plant photosynthesis, and our new research shows rising carbon dioxide concentrations largely drive this increase.

So, to put it simply, humans are producing more carbon dioxide. This carbon dioxide is causing more plant growth, and a higher capacity to suck up carbon dioxide. This process is called the “carbon dioxide fertilisation effect” – a phenomenon when carbon emissions boost photosynthesis and, in turn, plant growth.

What we didn’t know until our study is just how much the carbon dioxide fertilisation effect contributes to the increase in global photosynthesis on land.

But don’t get confused, our discovery doesn’t mean emitting carbon dioxide is a good thing and we should pump out more carbon dioxide, or that land-based ecosystems are removing more carbon dioxide emissions than we previously thought (we already know how much this is from scientific measurements).

And it definitely doesn’t mean mean we should, as climate sceptics have done, use the concept of carbon dioxide fertilisation to downplay the severity of climate change.

Read more: How to design a forest fit to heal the planet

Rather, our findings provide a new and clearer explanation of what causes vegetation around the world to absorb more carbon than it releases.

What’s more, we highlight the capacity of vegetation to absorb a proportion of human emissions, slowing the rate of climate change. This underscores the urgency to protect and restore terrestrial ecosystems like forests, savannas and grasslands and secure their carbon stocks.

And while more carbon dioxide in the atmosphere does allow landscapes to absorb more carbon dioxide, almost half (44%) of our emissions remain in the atmosphere.

More carbon dioxide makes plants more efficient

Since the beginning of the last century, photosynthesis on a global scale has increased in nearly constant proportion to the rise in atmospheric carbon dioxide. Both are now around 30% higher than in the 19th century, before industrialisation began to generate significant emissions.

Carbon dioxide fertilisation is responsible for at least 80% of this increase in photosynthesis. Most of the rest is attributed to a longer growing season in the rapidly warming boreal forest and Arctic.

Ecosystems such as forests act as a natural weapon against climate change by absorbing carbon from the atmosphere.Shutterstock

Ecosystems such as forests act as a natural weapon against climate change by absorbing carbon from the atmosphere.ShutterstockSo how does more carbon dioxide lead to more plant growth anyway?

Higher concentrations of carbon dioxide make plants more productive because photosynthesis relies on using the sun’s energy to synthesise sugar out of carbon dioxide and water. Plants and ecosystems use the sugar both as an energy source and as the basic building block for growth.

When the concentration of carbon dioxide in the air outside a plant leaf goes up, it can be taken up faster, super-charging the rate of photosynthesis.

Read more: CO₂ levels and climate change: is there really a controversy?

More carbon dioxide also means water savings for plants. More carbon dioxide available means pores on the surface of plant leaves regulating evaporation (called the stomata) can close slightly. They still absorb the same amount or more of carbon dioxide, but lose less water.

The resulting water savings can benefit vegetation in semi-arid landscapes that dominate much of Australia.

We saw this happen in a 2013 study, which analysed satellite data measuring changes in the overall greenness of Australia. It showed more leaf area in places where the amount of rain hadn’t changed over time. This suggests water efficiency of plants increases in a carbon dioxide-richer world.

Young forests help to capture carbon dioxide

In other research published recently, we mapped the carbon uptake of forests of different ages around the world. We showed forests regrowing on abandoned agricultural land occupy a larger area, and draw down even more carbon dioxide than old-growth forests, globally. But why?

Young forests need carbon to grow, so they’re a significant contributor to the carbon sink.Shutterstock

Young forests need carbon to grow, so they’re a significant contributor to the carbon sink.ShutterstockIn a mature forest, the death of old trees balances the amount of new wood grown each year. The old trees lose their wood to the soil and, eventually, to the atmosphere through decomposition.

A regrowing forest, on the other hand, is still accumulating wood, and that means it can act as a considerable sink for carbon until tree mortality and decomposition catch up with the rate of growth.

Read more: Forest thinning is controversial, but it shouldn’t be ruled out for managing bushfires

This age effect is superimposed on the carbon dioxide fertilisation effect, making young forests potentially very strong sinks.

In fact, globally, we found such regrowing forests are responsible for around 60% of the total carbon dioxide removal by forests overall. Their expansion by reforestation should be encouraged.

Forests are important to society for so many reasons – biodiversity, mental health, recreation, water resources. By absorbing emissions they are also part of our available arsenal to combat climate change. It’s vital we protect them.

Vanessa Haverd receives funding from the National Environmental Science Program

Benjamin Smith's contributions to research reported here were supported in part by Modelling the Regional and Global Earth System (MERGE), a Strategic Research Area of Lund University, funded by the Swedish Government through the Swedish Research Council.

Matthias Cuntz was supported by a grant overseen by the French National Research Agency (ANR) as part of the "Investissements d'Avenir” program, LabEx ARBRE (ANR-11-LABX-0002-01), and by funding from the ERA-NET Sumforest project ForRISK, funded in France through ANR (Grant No. ANR-16-SUMF-0001-01). Sumforest was funded by the European Union under Grant Agreement No. 606803.

Pep Canadell receives funding from the Australian National Environmental Science Program, and the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation

Authors: Vanessa Haverd, Principal research scientist, CSIRO

| < Prev | Next > |

|---|