from shutterstock.com

from shutterstock.comAustralia must do better in school education. Following our worst ever results in international tests last year, politicians are keen to act, and quickly. But Australia has had any number of educational reforms over the past few decades, and our grades keep slipping.

We need a much more systematic approach. Many teachers and schools are already doing great things and delivering outstanding results; but this practice is too piecemeal, too isolated.

Among other things, becoming more systematic means making better use of our top teachers – those helping students flourish and who can guide other teachers to a similar path for success.

A Grattan Institute report released today, Top teachers: sharing expertise to improve teaching, shows the way.

What is happening already

We aren’t the first to have the idea of making better use of top teachers.

Over the past few decades, Australia’s education systems and schools have invested in a smorgasbord of programs focused on instructional leadership.

These include Primary Maths Specialists (a federal professional learning program for teachers), Instructional Leaders in NSW (where instructors work with teachers to build student and teacher capacity in literacy and numeracy) and Learning Specialists in Victoria (a career pathway for highly skilled teachers to help improve the practice of other teachers).

Read more: Aussie students are a year behind students 10 years ago in science, maths and reading

These initiatives have all been well-intentioned. But they haven’t all been well-executed. For instance, the national Advanced Skills Teacher scheme in the 1990s was intended to increase top-end pay for only the highest-performing teachers. But in Victoria, virtually everyone who applied got the pay rise.

Other initiatives have been ad hoc, rather than becoming part of the daily work of teaching. None have had the scale and continuity Australia needs – or that high-performing systems already have, such as the Master Teacher roles that are part of Singapore’s expert career track.

A big disconnect between theory and practice

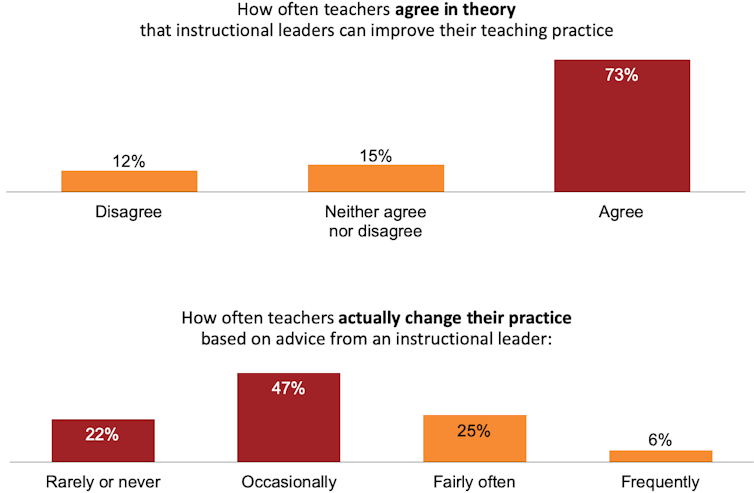

We surveyed 700 teachers, instructional leaders and principals across Australia to find out the impact of instructional teachers on the ground.

Three-quarters of the teachers said they valued guidance from instructional leaders, but fewer than a third regularly changed what they did in response.

Grattan Institute

Grattan InstituteIt’s not clear what causes this disconnect. But (self-identified) instructional leaders did tell us they were allocated too little time to do the job properly. Nearly half of them received no initial training when they started the job, and nearly two-thirds had no oversight from external experts.

And most are hired as generalists, which means they don’t get specific on how to teach particular subjects well.

What our model looks like

Unless something changes, we should expect this disconnect to continue. This was recognised in two recommendations in the 2018 “Gonski 2.0” report: better teacher career paths, and more effective teacher professional learning. Our new report shows how to do both in one go.

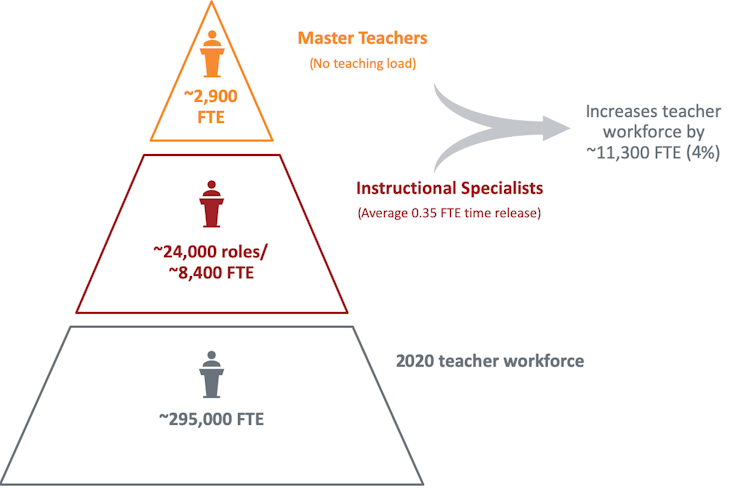

Our model would create two new types of teaching job, with an elite cohort of 2,500+ Master Teachers and 20,000+ Instructional Specialists. That’s enough for three Instructional Specialists in a typical primary school, and nine in a typical secondary school.

Grattan Institute

Grattan InstituteMaster Teachers would work across schools as the overall leaders in their subject. They would mentor and support Instructional Specialists, who work in schools to develop and support other teachers. And they would do this at scale: we are proposing one Instructional Specialist for every ten teachers, and one Master Teacher for every eight Instructional Specialists.

The new roles would help spread evidence-informed teaching practices, and generate new research in high-priority areas.

These are big roles and should be paid accordingly: Instructional Specialists up to A$140,000 per year ($40,000 more than the top standard rate for teachers) and Master Teachers $180,000 per year.

And to do the job well, Master Teachers and Instructional Specialists need to have the right skillset:

- strong teaching capability, proven by certification under the Australian Professional Standards for Teachers as a Highly Accomplished or Lead Teacher

- a strong understanding of how to teach their specialist subject, sometimes called pedagogical content knowledge, or PCK

- strong capabilities to lead adult learning, including the emotional intelligence to have difficult conversations.

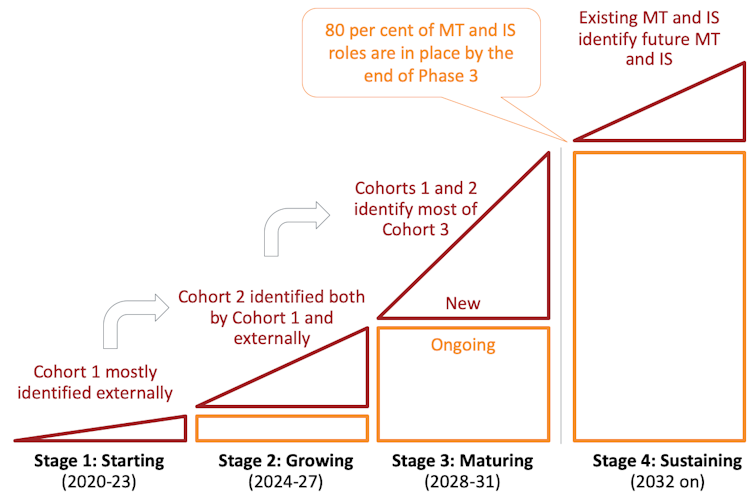

These skills take time to develop, so the model should be implemented using a four stage process, reaching 80% of full operating capacity by 2032.

Grattan Institute

Grattan InstituteTransforming school education

This model would transform school education, further professionalise learning and lead to students gaining about 18 months of extra learning by age 15.

It will take time, but imagine a child who just started their first year at school. By 2032, when she starts year 12, Australia could have transformed how teachers learn on the job, with teachers benefiting from more than one hour a week with an Instructional Specialist in their subject area.

Read more: Estonia didn't deliver its PISA results on the cheap, and neither will Australia

Schools would get access to the deep expertise of Master Teachers across a wide range of subjects. And systems would be better placed to learn and improve at scale.

The path is affordable

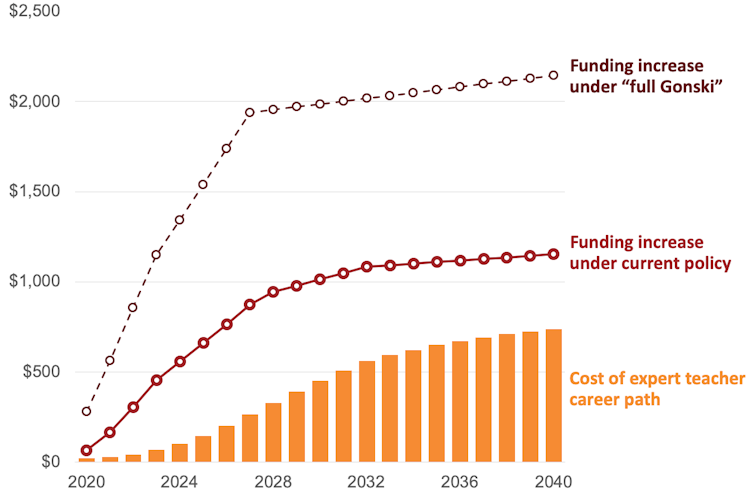

By 2032, the expert teacher career path would cost $560 per student per year. Meanwhile, under the 2019 National School Reform Agreement, the average government school is set to get an extra $1,100 per student per year by 2032.

This means government schools in most (but not all) states can pay for this proposal from within projected funding increases. And it would be a much better use of the extra money than just giving every teacher a 4% pay rise, or reducing class sizes by one student.

If government schools got 100% of what the funding formula says they actually need (the “full Gonski”), they could afford this and more.

Grattan Institute

Grattan InstituteNon-government schools have received generous funding increases over the past decade, and should fund this model out of their existing resources.

We want our children to have a fantastic education, but we haven’t given our teachers the support they need to deliver it, and it shows. We must get serious about a better system for improving teachers. Our new report shows how it could be done, and proves it is affordable.

Grattan Institute began with contributions to its endowment of $15 million from each of the federal and Victorian governments. In order to safeguard its independence, Grattan Institute’s board controls this endowment. The funds are invested and Grattan uses the income to pursue its activities.

Authors: Peter Goss, School Education Program Director, Grattan Institute

| < Prev | Next > |

|---|