Cromo Digital/Shutterstock

Cromo Digital/ShutterstockThe concentration of growth in major cities, driven by the knowledge economy and the changing nature of work, may also increase their social inequality. Our research looked at cities in the US and Australia. We compared measures of the knowledge economy and social vulnerability of their metropolitan areas and plotted them together.

Cities with above-average knowledge economies and below-average levels of social vulnerability are better placed to cope with the dual challenges of technological change and social inequality. Australia has only two cities in this category.

Australia’s biggest cities score high on knowledge economy capacity but also have high levels of social vulnerability. And some cities score poorly on both measures. This makes them doubly vulnerable to economic change and social inequality.

Read more: The Knowledge City Index: Sydney takes top spot but Canberra punches above its weight

Winners and losers in the one city

One factor in these contrasting trends of concentrated growth and rising social vulnerability is the changing nature of work. Cities are the site of the Fourth Industrial Revolution as the world economy clusters in major centres. It’s driven by the benefits of agglomeration – the productivity and efficiency gains from having many producers and people located near one another.

Already, 600 cities generate 60% of global economic output. The world has 21 mega-cities of over 10 million people compared to three in 1975. By 2040, 65% of the world population will live in cities.

In the US, jobs were lost all over the country during the Great Recession of 2007-09. But the recovery is concentrated in 25 urban cores. Some 60% of US job growth is expected to take place in these centres.

This over-concentration of employment opportunities may lead to social inequality and vulnerability within these cities. At the same time, other older and smaller cities have struggled to revamp their economies.

In Australia, too, the top five capital cities are growing bigger. Growth is dominated by Sydney and Melbourne, but economic and social inequalities are increasing.

Read more: Rapid growth is widening Melbourne's social and economic divide

Despite economic growth, homelessness is increasing in both Australian and US cities. For some US cities such as Los Angeles, Seattle and San Francisco, it is at a tipping point. These same cities are home to the most educated and richest citizens too.

How do US and Australian cities compare?

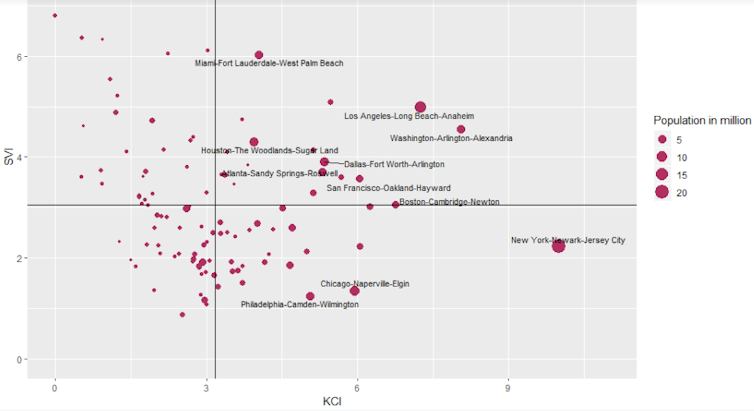

Combining various socioeconomic and demographic data (including Australian Census, US Census, American Community Survey and IPUMS data) at the metropolitan level, we created a Knowledge Cities Index (KCI) and Social Vulnerability Index (SVI). The chart below plots the KCI and SVI scores of 104 US metropolitan centres.

Knowledge Cities Index (KCI) and Social Vulnerability Index (SVI) of US cities. Higher KCI is to the right of the average line, higher SVI is above the average line.Author provided

Knowledge Cities Index (KCI) and Social Vulnerability Index (SVI) of US cities. Higher KCI is to the right of the average line, higher SVI is above the average line.Author providedThe middle two lines show the averages of these scores. Cities with higher knowledge city scores (right side of the line) and lower social vulnerability scores (below the line) are better placed to cope with the dual challenges of technological shift and social vulnerability. These cities include New York-Newark-Jersey City, Chicago-Naperville-Elgin, Baltimore-Columbia-Towson, and Boston-Cambridge-Newton.

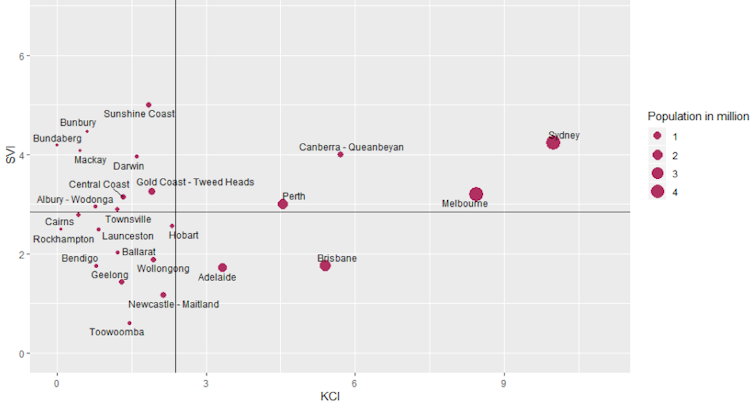

The chart below shows only two Australian cities – Brisbane and Adelaide – are in this category.

Knowledge Cities Index (KCI) and Social Vulnerability Index (SVI) of Australian cities. Higher KCI is to the right of the average line, higher SVI is above the average line.Author provided

Knowledge Cities Index (KCI) and Social Vulnerability Index (SVI) of Australian cities. Higher KCI is to the right of the average line, higher SVI is above the average line.Author providedCities with higher KCI scores but also higher SVI scores include Sydney, Melbourne, Canberra and Perth.

Some major US metro areas in this category are San Jose-Sunnyvale-Santa Clara, Washington-Arlington-Alexandria, North Port-Sarasota-Bradenton, Miami-Fort Lauderdale-West Palm Beach and Washington-Arlington-Alexandria. These cities are doing well in terms of knowledge generation and innovation, but have greater inequality and social disparities among their residents. These cities need strategies and policies to make themselves more inclusive and resilient.

The benefit of agglomeration economics may concentrate and benefit knowledge workers while segregating them from the rest of the society and increasing inequality.

Read more: What did the rich man say to the poor man? Why spatial inequality in Australia is no joke

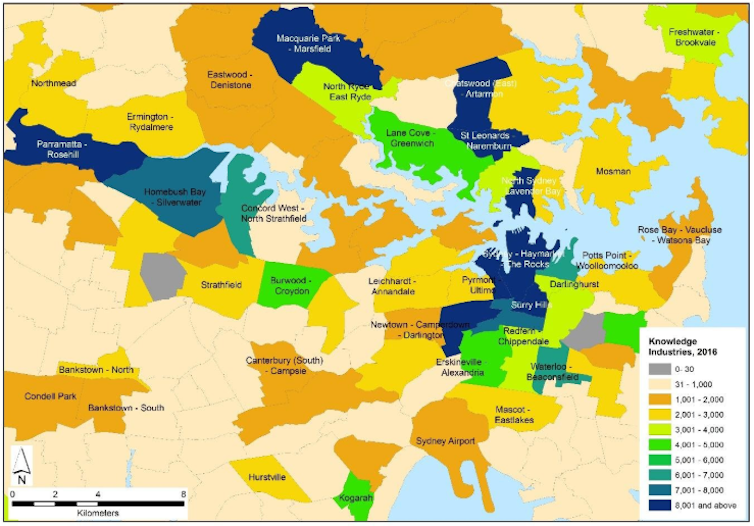

The map below shows the concentration of knowledge industries in Sydney. Sydney CDB has the highest concentration for most of the knowledge industries, except high-tech manufacturing.

Distribution of knowledge industries in Sydney metropolitan area.Data: ABS, 2016, Author provided

Distribution of knowledge industries in Sydney metropolitan area.Data: ABS, 2016, Author providedWe found some cities with very low KCI scores and high SVI scores. US examples include McAllen-Edinburg-Mission, Las Vegas-Henderson-Paradise, Portland-South Portland and Memphis. In Australia, cities in this category include Sunshine Coast, Bunbury, Central Coast, Townsville and Gold Coast-Tweed Heads.

These cities are the worst off. Their lack of knowledge capacities and high social inequality make them highly susceptible to both technological shifts and social vulnerability. Solid strategies and policies are needed to increase the knowledge bases and improve the social conditions of these cities.

What does this mean for policy?

One suggested solution is polycentric cities. But this approach depends on overcoming the challenge of coordinating transport with land uses.

Read more: Our big cities are engines of inequality, so how do we fix that?

The knowledge economy is increasingly important for cities to compete in the age of automation. But it can also compound the risk of increased social exclusion or vulnerability. Affected cities may then become less capable of withstanding impacts on other frontiers of social change.

The belligerent rate of automation may make the situation worse. Despite its cost-efficiencies, automation has other human costs.

Read more: Vital Signs: the end of the checkout signals a dire future for those without the right skills

These impacts require policy intervention. The two indices of our study examine both the urban opportunities and the downsides of inequality and social vulnerability that the knowledge economy creates. The policy challenge will be how to make socially vulnerable populations more resilient to the changing nature of work and reduce its negative impacts.

Read more: The fourth industrial revolution could lead to a dark future

Dr. Sajeda Tuli receives funding from Australian-American Fulbright Commission.

Shakil Bin Kashem does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Authors: Sajeda Tuli, Fulbright Scholar, Institute for Governance and Policy Analysis, University of Canberra

| < Prev | Next > |

|---|