Designing schools to accommodate students with disabilities is a complicated task and needs a lot more research than what is out there.from shutterstock.com

Designing schools to accommodate students with disabilities is a complicated task and needs a lot more research than what is out there.from shutterstock.comAustralia has scheduled up to A$11 billion on new schools and facility upgrades between 2016 and 2026. We need as many as 750 new schools to accommodate an additional 650,000 students.

Part of this spend must go towards improving school facilities, especially for students with a disability. In 2017, around 18.8% of school students in Australia were provided with adjustments at school – to participate on the same basis as other students – because of disability. The majority of these attend mainstream public schools.

This means every school (not just those for students with special education needs) should be designed with students of varying abilities in mind. We need to find ways to make all schools inclusive so children with mild and severe disabilities are not disadvantaged by facilities or services.

Read more: Most Australian teachers feel unprepared to teach students with special needs

School facility design has not kept pace with Australian inclusive education policies over past decades. Considering the diverse needs of children with disability, inclusive school architecture needs to learn from the best of what already exists to improve learning spaces for all students.

Vague universal principles

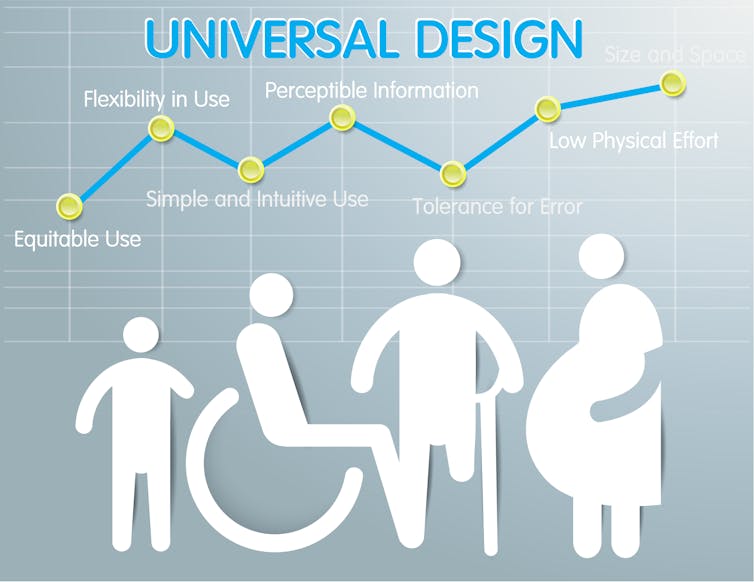

Designing more inclusive schools is possible, but complicated. When a school is designed and built in Australia, architects are often directed to follow the 7 Principles of Universal Design.

The principles of universal design don’t offer specific guidance on how to achieve it.from shutterstock.com

The principles of universal design don’t offer specific guidance on how to achieve it.from shutterstock.comThese include:

equitable use (the design must be useful to people of diverse abilities)

flexibility in use (the design must accommodate a range of preferences and abilities)

simple and intuitive use (the design can be easily understood by everyone)

perceptible information (there is effective communication on how to use the design, regardless of the user’s limitations)

tolerance for error (the design minimises accidents)

low physical effort (the design can be used without causing fatigue)

size and space for approach and use (anyone can reach anything regardless of their size or height).

These are useful as a general guide but they are too abstract to offer direction for designers, especially when student needs may shift from one year to the next.

Some examples

Two schools, Officer Specialist School in Australia and The Willows School (P-12) in the UK, offer tips about designing better facilities for inclusive education. Each sit on a mainstream school site, allowing disabled students to share facilities and participate in mainstream learning where possible or deemed appropriate.

Officer Specialist School provides adaptable facilities and spaces to respond to varying and sometimes competing needs. These include classrooms that can be configured to suit individual students’ learning needs through mobile furniture and adaptive technologies. Tactile walls and pause places where students can stand back and get their bearings play a crucial role too.

Read more: How autism-friendly architecture can change autistic children's lives

The school has designed visual and performing arts spaces for restricted mobility, hearing and sight impairments. Consulting rooms are available for health-service delivery.

Outdoor spaces also offer varying degrees of challenge for motor skills development. Sensory environments are designed to stimulate and calm students at different times of the day. This could involve stimulus shelters for quiet time or sensory rooms for physical stimulation. Labyrinth-style walks are popular with students as calming settings.

At The Willows, one wing of the school provides facilities specifically for disabled students, including a multi-sensory environment (relaxing spaces that help reduce agitation and anxiety). There are also soft play rooms and classrooms with integrated ceiling hoists and specific heating needs for students sensitive to thermal conditions.

The school worked with disabled artists to create sensory elements. The results included textured patterns along walls that support navigation across the school.

What can we learn?

Both schools were designed through consultation processes involving families, educators and service providers. Architects took the time to build trust between key stakeholders and listen to their varied perspectives.

There is no ideal school design, nor any one school that exemplifies all that is best about design for inclusive education. Making conclusions about what works is also limited by a lack of structured evaluation programs.

We need more evidence to generate a better understanding of the complex needs of all students and the role of design in supporting inclusive education.

Designing explicitly for inclusion will benefit everyone. To do this properly will need commitment from governments and schools, feeding evidence-based insights back into school systems, consultations with disabled and other students and designs that are responsive, offering multiple solutions of learning spaces.

We are developing projects at the Learning Environments Applied Research Network and the Bartlett Global Centre for Learning Environments in collaboration with The DisOrdinary Architecture Project to find out what best works for students with disability, and indeed all students.

Scott Alterator receives funding from the University of Melbourne and Catholic Education Melbourne. He is affiliated with Learning Environments Australasia

Benjamin Cleveland receives funding from the University of Melbourne, Australian Research Council and Catholic Education Melbourne. He is affiliated with Learning Environments Australasia.

Jocelyn Boys receives funding from the UCL HEIF budget for work on urban schools and community innovation. She is affiliated with the Bartlett Global Centre for Learning Environments UCL and is a co-director of The DisOrdinary Architecture Project which co-develops inclusive design processes with disabled artists.

Authors: Scott Alterator, Research Fellow (Learning Environments Applied Research Network); Director at Innovation Design Education;, University of Melbourne

| < Prev | Next > |

|---|