Anna Spargo-Ryan carefully layers metaphors throughout The Paper House to blur the space between reality and imagination. Jean Carlo Emer /Unsplash, CC BY

Anna Spargo-Ryan carefully layers metaphors throughout The Paper House to blur the space between reality and imagination. Jean Carlo Emer /Unsplash, CC BYWhy do we tell stories, and how are they crafted? In this series, we unpick the work of the writer on both page and screen.

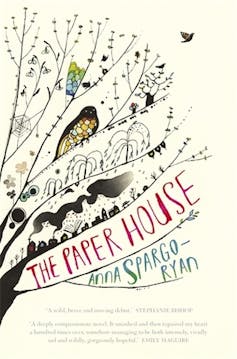

Anna Spargo-Ryan’s debut novel, The Paper House (2016), is a layered articulation of loss and grief, perception and reality. It explores the nature of reality as felt and lived by protagonist Heather – not always what the other characters consider as real.

The Paper House takes the reader into Heather’s means of escape: the almost mythical garden of her new house where she meets people, both real and unreal. The characters Heather meets help her to come to terms with grief, and allow her to repair fractured relationships. The journey takes Heather through hidden places in her new garden and through her memories of her childhood and her mother.

Spargo-Ryan employs figurative language and imagery as a structural device, enabling thematic concerns to become part of the way the novel is built. The nature of reality is considered not only through the narrative, but also through use of startling metaphors and exactingly vivid imagery.

Crafting metaphor

Most authors make use of metaphor when they write: something described as something else in order to draw a non-literal connection. To give an example from The Paper House: “The world and I collided, saucepans on a rack”. This expression allows the reader to imagine the violence, noise and antagonism.

Metaphors work to challenge or surprise readers to see the characters and topics under investigation in a new way.

In Spargo-Ryan’s novel, metaphors are used in conjunction with imagery, creating a unique picture in the mind of the reader.

I could hear the panic churning in his bone marrow and I wanted to run from the radiology department but equally I didn’t want to rupture and die in the hallway

Metaphor and imagery can be used to develop settings, characters and themes. The use of figurative language to develop themes demands a consistent thread – a structural use of metaphor and imagery.

In The Paper House, metaphors dovetail into concepts surrounding the nature of reality and the literal in opposition to the fabricated, misremembered or delusional.

I found myself collecting metaphors from within the book, plucking them like the flowers Heather draws in her sketchbook, pressing them between the pages of my journal for the simple joy of collecting something beautiful.

Spargo-Ryan’s use of metaphor expands beyond examples of comparison creating pictures (the streets “hiccupped with children”). Instead, these images dictate the reader’s whole experience of reality: a building block of the narrative challenging assumptions we make about what we are shown by the protagonist.

Slowly and gently, the reader becomes aware much of the reality we have been experiencing with Heather is not objectively real. It is merely her sense of reality. Heather’s book of drawings – currawong, lemon-scented tea tree, ironbark – turns out to be “page after page of a little girl’s face”.

Read more: Stories for hyperlinked times: the short story cycle and Rebekah Clarkson’s Barking Dogs

The genius of metaphor

Aristotle argued mastery of metaphor was a sign of genius. A well-formed metaphor can conjure a new way of seeing. Perhaps the idea of being a genius with metaphors also lies in the fact using figurative language can present writers with a number of pitfalls.

There is an art to writing metaphors and to their effective use. Spargo-Ryan uses the following sentence to pull together Heather’s memories of her father as a man broken by her mother’s mental illness:

He had looked at me with his heart in his eyes and his eyes in a hole, and his shoulders sagged at the corners, and his body was just a skeleton on a coat hanger.

The reader is left with a startling picture of a man worn down and eaten up by his love.

The difficulties writers sometimes have with metaphor can come down to a question of balance. The trap for authors lies in the trickiness in over- or under-extending the metaphor. If a metaphor is not taken far enough or is too close to the literal meaning, it might not be recognised as metaphor and feel inaccurate or jarring. Similarly, well-established metaphors (a “rollercoaster of emotions”) make writing clichéd.

Spargo-Ryan goes beyond Aristotle’s notion of genius.

At the very beginning of the novel, Heather and her husband suffer a shattering loss: “for five days we sent our bodies into the world without us”.

During this time, Heather describes herself as “a girl who had become a stocking” – and this insubstantiality is reflected in later descriptions of students. Young people are described as gathering “around tables and bus stops and any other anchor they could find”, as if their bodies alone are not enough to hold them to the ground.

Metaphors in this novel continually engage in a productive interplay developing thematic and structural considerations. The beauty of Spargo-Ryan’s writing ensures her metaphors work on a micro level but also on a macro level, developing content and theme.

One image reminds the reader of a previous one. The whole becomes greater than the sum of its parts. Spargo-Ryan’s metaphors act as a way of both supporting and structuring the narrative. Aristotle would approve.

Debra Wain does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Authors: Debra Wain, Academic in Professional and Creaive Writing, Deakin University

| < Prev | Next > |

|---|