Some things went wrong and some things went right. The resulting current account surplus is neither good nor bad.Shutterstock/ABS

Some things went wrong and some things went right. The resulting current account surplus is neither good nor bad.Shutterstock/ABSAustralia has been in a current account deficit – paying more money out to the rest of the world than it took in – for 44 straight years, since September 1975.

Until today. The update from the Bureau of Statistics released on Tuesday shows that in the three months to June Australia actually took in more from the rest of the world than it paid out: A$5.9 billion more, after what for most Australians (most are under the age of 40) was a lifetime of paying out more.

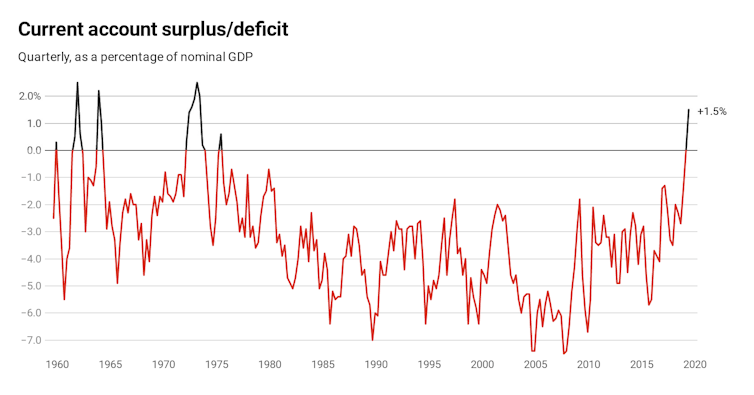

June 2019 percentage is an estimate. The June quarter GDP will be released on Wednesday.Source: ABS 5302.0, ABS 5206.0

June 2019 percentage is an estimate. The June quarter GDP will be released on Wednesday.Source: ABS 5302.0, ABS 5206.0Why has it happened, and how did we get away with doing the opposite for so long?

First, the long-term story. It couldn’t happen to an individual. No one person can get away with taking more in from the rest of the world than they pay out for long.

It was the idea that a nation is like an individual that allowed the then treasurer Paul Keating to spend a good deal of the 1980s arguing that Australia was living beyond its means.

As the drumbeat of a steadily growing current account deficit grew louder and it approached 5-6% of GDP, on May 14, 1986, he infamously told radio presenter John Laws that Australia was in danger of becoming a banana republic:

I get the very clear feeling that we must let Australians know truthfully, honestly, earnestly, just what sort of international hole Australia is in. It’s the prices of our commodities — they are as bad in real terms (as) since the Depression.

If this government cannot get the adjustment, get manufacturing going again, and keep moderate wage outcomes and a sensible economic policy, then Australia is basically done for. We will just end up being a third-rate economy … a banana republic.

To get spending down, and thus reduce the current account deficit, he tightened the budget and encouraged the Reserve Bank to push interest rates to stratospheric levels. The cash rate hit 18% before helping push Australia into recession .

And for what? The current account deficit continued. It averaged 4% of GDP throughout the 1990s and 2000s. But life went on. The economy recovered, the Bureau of Statistics stopped publishing monthly current account figures (moving to quarterly), the figures became little watched and the pundits and politicians turned their attention elsewhere.

Read more: Cabinet papers 1990-91: lessons from the recession we didn’t have to have

With the benefit of hindsight it is clear that the deficits weren’t because of any deficiency on the part of Australians. Reserve Bank deputy governor Guy Debelle explained last week that Australians weren’t spending an unusual amount compared to what they earned. They were “about on par with many other advanced economies”.

The current account deficits were largely the result of money flowing out as returns on investments in Australia. Australia had “a lot of profitable investment opportunities”. Foreigners either lent to Australian businesses or invested in Australian businesses and returns flowed out each month, as they should have.

It came to be known as the “consenting adults” theory of international finance. It’s practical message was: “nothing to see here, move along”.

So what’s changed?

In 2017 and 2018 the current account deficit shrank to around 2% of GDP. We now know that in the three months to June this year it moved into surplus.

Much of it is because we’ve been earning more from mining exports. We’re both exporting more tonnes and getting paid more for each one.

And just lately mining has helped in another way. The so-called mining investment boom is winding up. We are no longer importing enormously expensive machines to build gas terminals and the like.

And it’s more than mining. Export income from services such as education and tourism now accounts for 21% of all exports, up from 17% in the 1980s. Purists will complain that education and tourism aren’t actually exported, but as far as the national accounts are concerned, they are. Even though the teaching and hospitality takes place in Australia, it is paid for in foreign dollars that bring more money into the country relative to what is going out.

And there’s something else.

We are becoming like the US

As popular as Australia remains as a destination for foreign investment, since 2013 Australians have been investing even more in foreign businesses than foreigners have been investing in Australian businesses.

It is superannuation that’s done it: a record A$2.9 trillion worth.

Debelle put it this way:

This largely reflects the significant allocation to foreign equity by the Australian superannuation industry together with the fact that the superannuation sector is relatively large as a share of the Australian economy.

Australia has become a net foreign investor rather than a net recipient of foreign investment, almost certainly for the first time ever.

Debelle says it has made Australia come to resemble the United States. We receive more in dividends from overseas than we pay out in dividends to overseas share holders.

We’re still a magnet for foreign dollars

We are still a huge destination for foreign lending, increasingly in the form of lending to the Australian government rather than to Australian companies, as safety-conscious foreigners push locals out of the way to buy more and more Australian government bonds.

Foreign ownership of Australian government bonds has climbed from around 40% to 60% since the early 2000s.

The interest rate foreigners are prepared to accept in order to hold Australian 10 year bonds has fallen below 1% (which in its own way assists in keeping the current account deficit low).

Read more: Revisiting the banana republic and other familiar destinations

How long the current account surplus lasts will depend on the investment policies of our super funds (the better the prospects are overseas, the higher the surplus will be), the strength of our economy (the weaker is consumer spending, the higher our current account surplus will be) and export prices and volumes (which are mainly beyond our control).

Yes, we’ve current account surplus. It would have once been a cause for celebration. Now that we’ve got it, it’s not looking that special.

Peter Martin. does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Authors: Peter Martin., Visiting Fellow, Crawford School of Public Policy, Australian National University

| < Prev | Next > |

|---|