Another issue is that pre-polling gives an advantage to the major parties over the smaller ones, due to the latter having fewer resources.AAP/Bianca de Marchi

Another issue is that pre-polling gives an advantage to the major parties over the smaller ones, due to the latter having fewer resources.AAP/Bianca de MarchiOn the morning of the last Monday in April, 2019, federal election officials opened the doors of more than 500 pre-poll voting centres around Australia, and waited for the voters to turn up. It was the first day of the three-week early voting period leading up to the May 18 election day.

They didn’t have to wait long. By the end of the day, 123,793 voters had walked through the doors and cast their votes – more than the enrolment of an average House of Representatives electorate, and a record number for the first day of pre-polling.

Read more: Three weeks of early voting has a significant effect on democracy. Here's why

That evening, the rush to the polls attracted comment at the first leaders’ debate. Opposition leader Bill Shorten claimed people were voting early because they wanted “change”; Prime Minister Scott Morrison insisted it showed people “deserve” to know the cost of opposition policies.

In turn, pre-polling attracted more media attention than in previous campaigns.

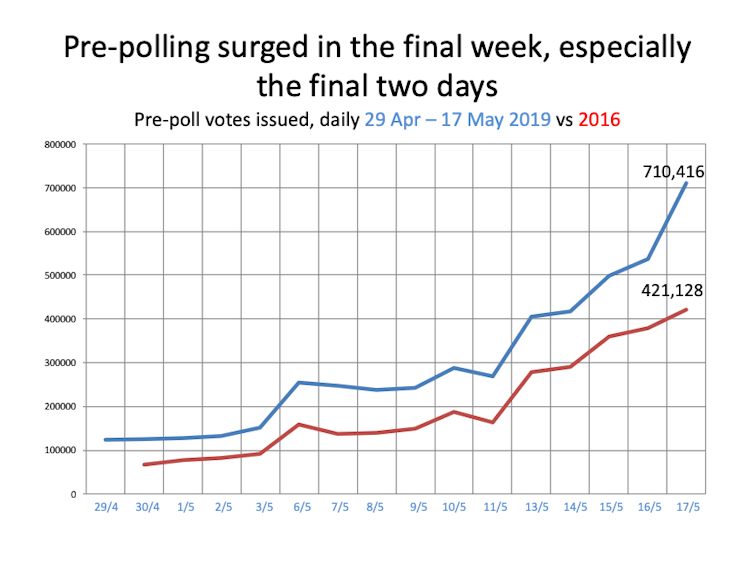

Pre-polling increased steadily through the campaign, culminating on the last Friday with 710,000 pre-poll voters. The total for the full three weeks was 4.7 million, or 31.6% of total turnout.

Picture.Author supplied

Picture.Author suppliedAnother 1.6 million voted early by post. In short, nearly four in ten voters decided, before the campaign had finished, that they had heard enough and were ready to cast their votes.

Pre-polling has come of age. While it has been on the rise in recent electoral cycles, it reached record levels federally in 2019. Casting a vote before election day has been transformed, over a very few electoral cycles, from the occasional practice of a limited number of eligible voters to the habitual form of electoral participation of a large minority of the electorate.

Who votes early?

Despite the popularity of pre-polling, there is a puzzling unevenness about it. Some voters love it more than others. Australian Electoral Commission data show the Northern Territory, with its own particular geography and demography, had the highest form of pre-poll voting at 42.9% of turnout. Victoria (37.2%), ACT (36.5%) and Queensland (35.6%) were well above average, while Tasmania (19%), SA (21.7%) and WA (22.9%) lagged. NSW sat just below the national average at 30.1%.

While the rates of all states and territories were lower in 2016, their relative percentages were very similar.

Pre-polling is particularly strong in rural electorates. Ten of the 15 electorates in the country with the highest pre-poll percentage were rural electorates, despite the fact that the AEC has less than one third of seats classed in this category. All 15 of these seats are in Victoria, NSW or Queensland.

By contrast, 13 of the 15 electorates with the lowest percentage of pre-poll voters came from WA, Tasmania and South Australia, and just three of these were from outside the main metropolitan areas.

In terms of political allegiance, the inclination of early voters is well known: those voting early have tended to lean towards the Coalition. As psephologist Peter Brent has shown, this gap has only widened in recent electoral cycles, despite the growing number of early voters.

In 2004, the Coalition did 4% better in early voting than voting on election day; by 2019 this gap rose to just over 5%. There is strong evidence for Coalition mobilisation of postal voters, with 312,391 postal vote applications received from Coalition parties in 2019, and just 149,582 from the Labor party.

The reasons why people vote early are still widely debated, but the key reasons are convenience and access.

There is also evidence that indicates older people like voting earlier. Such arguments are borne out in those figures, given the older demographics of rural areas, and the greater distances that voters may need to travel to access voting booths.

Has deregulating early voting made a difference?

One factor cited as an explanation for the increase in early voting is the easing of restrictions on the practice. A number of jurisdictions including Victoria (2010), Queensland (2015), and Western Australia (2016) have made it easier to vote early at pre-poll booths for state elections by removing the need for voters to provide justifications for doing so. The rationale when doing so has been that this would make such voting forms more accessible.

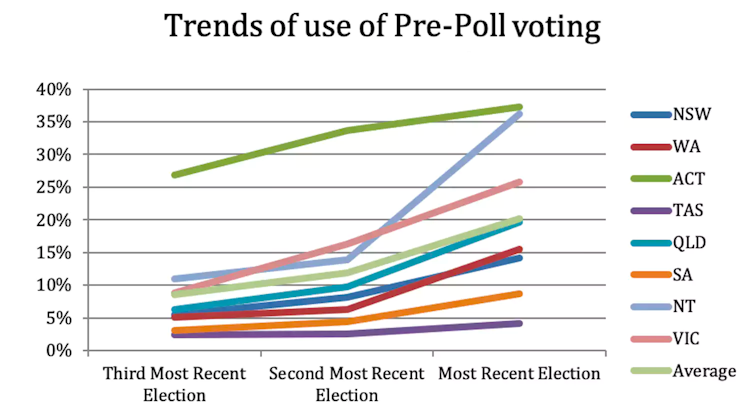

While we would expect to see these jurisdictions record higher levels of pre-poll voting, the outcomes of these changes in legislation have been mixed (see chart two).

Author supplied, Author provided

Author supplied, Author providedVictoria’s 2018 state election recorded the highest levels of pre-poll voting of any state, at 37.29%, and this may be linked to their decision to deregulate the practice earlier than elsewhere. But at their last state elections, WA, while recording a boost in postal voting (which remains regulated) had a pre-poll rate of 15.47%, and Queensland of 19.64% - both still well short of Victoria.

While pre-poll voting in Queensland and WA increased after deregulation, it did not increase any more markedly than other jurisdictions that retained regulation.

Moreover, each of these jurisdictions recorded a prepoll rate for the 2019 Federal election equal to, or higher than, the previous state election, despite the Commonwealth retaining the need for voters to justify their decision to do so.

While in Victoria the rate was almost identical, in WA and Queensland the Federal rate of pre-poll was much higher.

Conclusions: unexpected implications

An examination of early voting data, particularly around the practice of pre-polling, demonstrates clear but unexplained trends. Tasmania, WA and South Australia lag well behind the other states and territories in pre-polling. There is even clearer unevenness within states, where rural and regional voters are voting early in significantly higher numbers than their metropolitan counterparts.

The data also indicate that making forms of early voting more accessible (such as by deregulating pre-polling) has in itself not led to marked increases in the practice.

Read more: Difficult for Labor to win in 2022 using new pendulum, plus Senate and House preference flows

What we also know is that the large rates of early voting have changed the relationship between voters and the people or parties they are choosing to vote for, in that many voters cast their ballots before the parties have released all their policies.

Other unanticipated effects have emerged. In 2019, we saw many early voters casting votes for candidates who were later disendorsed by their own parties.

This arises because the early voting period occupies the maximum available time on the campaign calendar, beginning as soon as possible after close of nominations. This may create a dysfunction between voters and the parties candidates claim to represent on the ballot.

Pre-polling also leads to uneven playing fields between major parties as opposed to minor parties and independents, due to the latter having fewer resources.

There are also additional challenges faced by electoral commissions in the provision of pre-poll centres and staff to manage this surge. This research has been published in The Conversation and in a previous report on voting flexibility late last year.

The increased uptake of early voting in 2019 only exacerbates these implications, many of which may not have been anticipated until recently.

While early voting is important in providing greater accessibility to voters and encouraging turnout, thought should be given to reviewing the full implications through the Joint Standing Committee on Electoral Matters (JSCEM).

One possibility is to retain the current forms of early voting but limit the pre-poll period to two weeks rather than three. This would retain flexibility for voters, but make the process more manageable for all the stakeholders concerned.

Stephen Mills and Martin Drum's research was funded through the Electoral Regulation Research Network which is jointly funded by the New South Wales Electoral Commission, the Victoria Electoral Commission, and Melbourne Law School. Neither author works for, consults, owns shares in or receives funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Martin Drum does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Authors: Stephen Mills, Hon Senior Lecturer, School of Social and Political Sciences, University of Sydney

| < Prev | Next > |

|---|