Not everyone trusts that science will bring benefits to society. from www.shutterstock.com

Not everyone trusts that science will bring benefits to society. from www.shutterstock.comNew research shows that despite differences in their funding commitments, major political parties in Australia – the Coalition, Labor and the Greens – see science and technology as important aspects of our economy and future prosperity.

But that’s not enough.

It’s also crucial that the Australian public is able to have a say on priorities for scientific research and its applications. The social license of science depends on being able to engage with the public. Without this, scientists and other experts risk losing public trust.

This could have real implications for achieving the public good when it comes to emerging disruptive technologies (like robotics and AI), the environment (including climate change) and more.

Read more: Why do some people not care about science?

Former Prime Minister Tony Abbott recently pointed to tensions between government, the public and scientists, saying “we sub-contract too much out to experts already”. So how can we build, and not erode, trust in Australia’s scientists and other experts?

We recently worked with scientists to distil priorities they think should be front and centre in building a trusting relationship between science and the public.

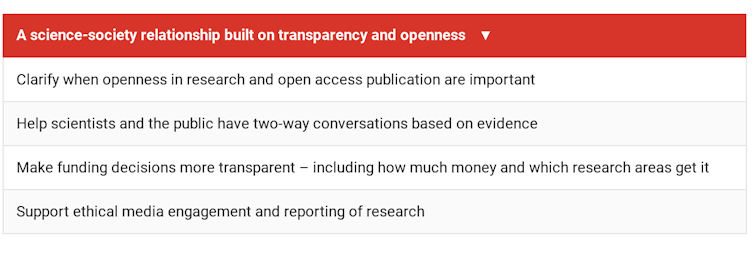

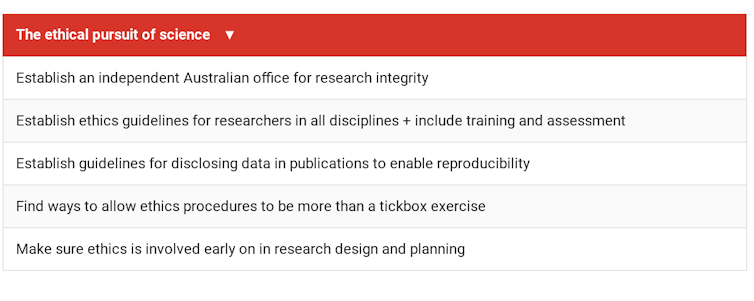

They say that improvements can be made in:

- transparency

- high ethical standards

- two-way dialogue between scientists and the public.

A new charter

The social license for science is not a “set and forget” exercise. As disruptive technologies emerge, scientists need to re-engage the general public to understand changing expectations and views about science.

With election 2019 in mind, late in 2018 the Australian Academy of Science (AAS) called for a new charter to re-set the relationship between science and government, and to identify fresh ways for the general public to be involved in science.

Read more: STEM is worth investing in, but Australia's major parties offer scant details on policy and funding

Focusing on key areas highlighted by the AAS, we adapted existing research methods to gather survey responses from 174 respondents across the science and innovation sector, and collated over 700 priority statements.

A group of 18 scientists – both senior and early career researchers across science domains – then gathered in Canberra on April 18 to work through the survey findings, and identify priorities for re-freshing scientists’ social licence. For this workshop exercise, we did a first cut of analysis and grouped the statements for similarity.

The survey data indicate the majority of respondents believe science should be based on transparency, openness, and meaningful dialogue with society. They also believe the ethical pursuit of research and innovation is important. However, the majority feel that current institutional arrangements don’t support these aspirations.

Read more: What it means to ‘know your audience’ when communicating about science

What do we need?

Participants in the workshop offered a set of priorities for action.

Author provided

Author provided Author provided

Author provided Author provided

Author providedHow the science sector can do better

Some of these principles don’t cover new ground – for example, some aspects were already contained in the 2018 release of the Australian Code for the Responsible Conduct of Research. Also many scientists would say that openness, engagement and integrity are already central to their work.

But there is a sense running through this list of priorities that the science sector could collectively be doing better. That perhaps some of the ways scientists engage with the public, open up their work for debate or reflect on ethical implications are limited by old assumptions.

Read more: Science is important but moves too fast: five charts on how Australians view science and scientists

Also, scientists will need a lot more support from science and policy institutions if they want to shake up the old ways of doing things.

We hope these results mark the beginning of a longer conversation – as well as some concrete actions – about what a social licence for science means, and what is needed to meet public obligations in doing good science.

Some of this is already happening internationally, as learned academies combine forces to speak to governments about tackling critical shared challenges posed by environmental change and new technologies. Scientists, they stress, need to prioritise meaningful conversations with citizens and policy-makers should do more to create the infrastructure to make this possible.

In Australia, it’s important the next government meets the challenge of refreshing the social licence between science, government and the many and diverse communities that make up our nation.

The research described in this article was designed and undertaken by a team of researchers from the Australian National University and The University of Queensland and CSIRO. The views expressed here are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of any other agency or organisation.

Joan Leach receives funding from The Australian Research Council. She also is Chair of the National Committee for History and Philosophy of Science at The Australian Academy of Science. The work reported in this article was supported by funding from CSIRO's Responsible Innovation Initiative and The Australian Academy of Science.

Matthew Herington has previously received funding from the Australian Government Endeavour Leadership Program, and the American Australian Association. The work reported in this article was supported by funding from CSIRO’s Responsible Innovation Initiative and the Australian Academy of Science.

Sujatha Raman has previously received research funding from UK agencies including the Leverhulme Trust, the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC), the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC) and the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BBSRC). The work reported in this article was supported by funding from CSIRO's Responsible Innovation Initiative and the Australian Academy of Science.

Authors: Joan Leach, Professor, Australian National University

| < Prev | Next > |

|---|