Among the many recommendations of the banking Royal Commission was a Board of Oversight for the two regulators in charge of financial institutions; the Australian Securities and Investments Commission and the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority: ASIC and APRA.

Since then APRA’s own internal review conducted by deputy chairman John Lonsdale and NSW Supreme Court Judge Robert Austin, Australian Competition and Consumer Commission commissioner Sarah Court and UNSW professor Dimity Kingsford-Smith has found APRA to be soft on enforcement and timid by comparison to its international peers.

Nonetheless, and to demonstrate that APRA still doesn’t get what it doesn’t get, its chairman used Tuesday’s release of the review to announce a new mantra. From now on, APRA is to be: “constructively tough”.

‘Constructively tough’?

It sounds like “tough but flexible”, a contradiction in terms if ever there was one. Despite its Royal Commission hammering, APRA still seems not to have internalised the message: fraud and theft are not up for negotiated settlement.

This is why a board of oversight is so necessary.

I have frequently argued in favour of such a reform: a regulator to regulate the regulators. Along with colleagues Karen Fairweather and John Tarrant, I was invited to make a submission to the Royal Commission detailing egregious examples of regulator inefficacy, and capture by, and subornation to, the industries they are meant to regulate. Included was a body of theoretical and empirical international scholarship suggesting that financial sector regulators are more susceptible to capture than regulators of other industries.

We argued that the gravity of the potential harm from crises, superimposed with the frailties – both observable and theoretical – of regulators, required enhanced safety in the form of an overseer to police the corporate police.

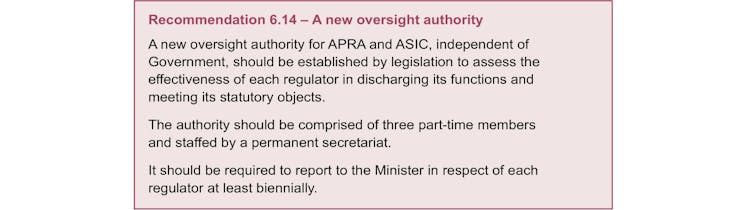

So it was encouraging to see our submission reflected in the commission’s recommendation for a board of oversight:

Final Report of the Royal Commission into Misconduct in the Banking, Superannuation and Financial Services Industry, February 2019

Final Report of the Royal Commission into Misconduct in the Banking, Superannuation and Financial Services Industry, February 2019Of concern, however, is that the commissioner elected to leave the details of how the board would work to parliament. It is here that the process faces its greatest risk: the risk of clumsy albeit well-intentioned implementation, all the way to purposefully bad implementation, fully intended to undermine the fundamental goals of the whole endeavour, and facilitated by equally captured and suborned politicians.

Politicians have a history of backing down

It has happened before. The 1991 report of the The House of Representatives Standing Committee on Finance and Public Administration entitled “Pocket Full of Change” recommended a banking code of practice, which was ditched at the last minute to be replaced by a different code written by the Australian Bankers’ Association. The result was a code that protected banks against their customers, while allowing them to virtue signal.

So far Treasurer Frydenberg has refused to commit to one of the single most necessary powers that such a board can possess: the power of public opprobrium. As far back as the late 1860s Charles Francis Adams Jr wrote of the need to subject captured and corrupted railroad commissions to the disinfecting power of sunlight; what Thomas McCraw, writing in the mid-1980s referred to as a Sunshine Commission.

Read more: Defence mechanisms. Why NAB chairman Ken Henry lost his job

The anti-viral power of public exposure has been amply demonstrated by the banking royal commission already. Heads have rolled: the chair, chief executive and group counsel at AMP. The chair and chief executive of the National Australian Bank (albeit after significant procrastination). Some entities have self-selected out of their business model. Others have self-selected out of the market entirely. Retail Super funds have haemorrhaged well in excess of one million members, and over $11 billion in funds.

But none of this fallout, none of it, is due to post-royal commission enforcement measures. It is all thanks to public opprobrium: sunshine.

Few things are as powerful as the power to shame

So it is of concern that the treasurer hasn’t yet made an unequivocal commitment to make public the board of oversight’s reports into the performance of our regulators, performance which to date has been weak enough, feckless enough, and incompetent enough to more than justify the royal commission.

Speaking to the ABC on February 4 in what might be some sort of Orwellian newspeak, Frydenberg would only say:

this new oversight board will be reporting to government and governments don’t operate in secret.

Sometimes they do, and especially when dealing with banks. APRA reports are routinely withheld form the public, making use of the secrecy provisions of the Banking Act.

Frydenberg should instead be mindful of the extensive protection his government has provided to the banking and retail super industry over the past five years, shielding them from the threat of inquiry by a royal commission up until the point when it was impossible to resist. It will serve no purpose to replace one protection racket with another. And that applies to both banks and super, something Labor’s Chris Bowen should keep in mind should he become treasurer.

Put simply, as we emerge from this dark, decade-long night of the most appalling dishonesty and wickedness in our financial sector, more than anything else, now we must ensure the sun shines.

Andrew Schmulow consults to Datta Burton and Associates and the Australian Institute of Superannuation Trustees. He has previously received funding from the South African Human Sciences Research Council, the Ernst and Ethel Eriksen Trust, the Harvard Law School, the University of the Witwatersrand, the University of Pretoria, and various universities in Australia. He is affiliated with Australian Citizens Against Corruption and the American Council on Consumer Interests.

Authors: Andrew Schmulow, Senior Lecturer, Faculty of Law, University of Wollongong

| < Prev | Next > |

|---|