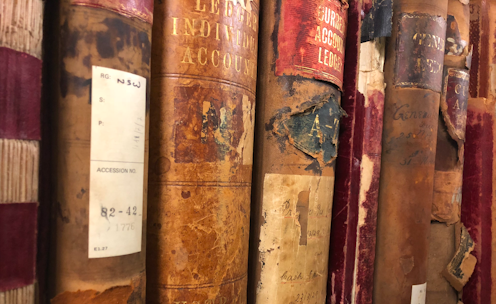

The first kangaroo-leather bound ledgers of what became Westpac, photographed in the Westpac archives.Westpac archives, Author provided

The first kangaroo-leather bound ledgers of what became Westpac, photographed in the Westpac archives.Westpac archives, Author providedOne of Australia’s biggest banks, currently under scrutiny at the royal commission, has a long history.

The Bank of New South Wales, which later became Westpac, was established in 1817 under a charter of incorporation signed by Governor Lachlan Macquarie. It was Australia’s first bank and first public company.

But there’s something brushed over in the official history. Its first depositor, Sergeant Jeremiah Murphy, put in an unusually large sum of money (far more than his official salary) three days before the bank opened.

Just as the banking royal commission has been using ledgers, transaction accounts, remuneration reports and meeting minutes to try to get inside the behaviour of today’s banks, I and my colleagues Jason L’Ecuyer, Tom Allinson and Tamson Pietsch examined kangaroo-leather-bound ledgers and microfilm of military paymaster reports to understand how the bank started and how some people were making money in early colonial Australia.

The results can be heard on the latest 2SER History Lab podcast. To many listeners, the findings will be unsettling.

Our investigation

Just like Antarctic ice core samples or ancient tree rings, financial documents capture and preserve events over time. Through them, we can grasp glimpses of the period in which they were created.

The bank’s ledgers show the growing wealth of early entrepreneurs, such as Mary Reiby, the convict-turned-merchant who appears on the Australian $20 bill.

In colonial accounts, we can also see the sale of liquor licences to Sydney’s first establishments, and infrastructure spending on bridges, wharves and hospitals.

There is even a schedule of prices for Australia’s first toll road out to Parramatta.

But the records also contain sobering evidence of darker aspects of Australia’s past.

Disturbingly, we can see financial payments to settlers and the military for punitive expeditions against Aboriginal Australians.

Why trust the accounts?

Financial records can shed light on what happened because of the meticulous manner in which they were prepared.

Military payslips were cross-referenced against muster sheets. Colonial payments were reviewed by committees.

Customer withdrawals were matched against signatures. Ledgers were periodically balanced. The bank’s own clerks ran the risk of having their pay docked for errors or poor penmanship.

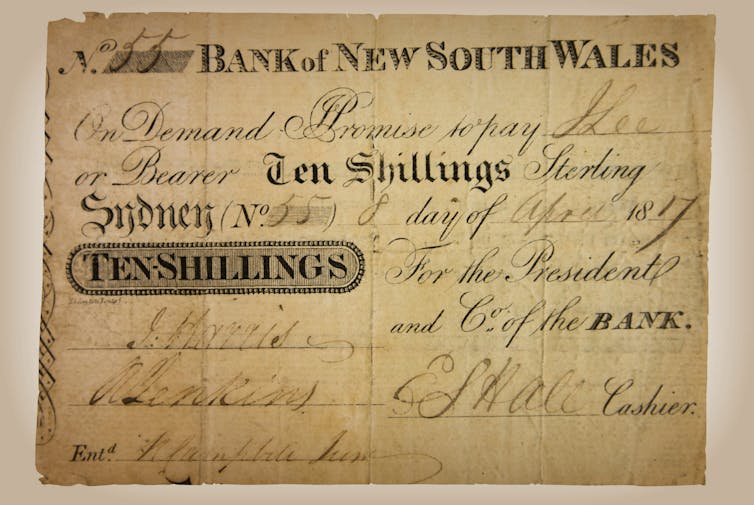

One fo the first banknotes issued by the Bank of New South Wales. April 8, 1817.© Australian Museum

One fo the first banknotes issued by the Bank of New South Wales. April 8, 1817.© Australian MuseumThese records also make for compelling sources because, ironically, most were never intended for outsider eyes.

They lack the vague, self-conscious or euphemistic language often found in public proclamations.

Instead, they were working documents.

They served particular functions, such as keeping track of a bank’s funds, maintaining fiscal control over regiments spread across an empire or managing the revenue and expenditure of an emerging colony.

To be effective they had to be accurate, comprehensive, and complete.

Holding to account

In the year before his mysterious deposit Sergeant Jeremiah Murphy was sent out by Governor Macquarie “in pursuit of natives”.

It is highly doubtful that Jeremiah Murphy ever anticipated that some 200 years later, a team of researchers and radio producers would pore over his financial dealings to piece together an account of his movements and decisions.

Yet since his time, there has been an enormous expansion in both the legal and regulatory compliance requirements to maintain and preserve internal records, as well as avenues for public scrutiny, media attention and inquiry.

Read more: So what's a secretary to do? Banking Royal Commission raises questions about what's in minutes

Bankers, like all of those who work in organisations and colonial institutions, should be mindful of the traces their actions leave behind in mere administrative records.

Sooner or later someone might look at their books.

The Bank, The Sargent and His Bonus is a collaboration between 2SER 107.3, the Australian Centre for Public History and the UTS Business School. It is available for download through the Think Business Futures and History Lab podcasts.

Nicole Sutton does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Authors: Nicole Sutton, Lecturer in Accounting, University of Technology Sydney

| < Prev | Next > |

|---|