A year ago, on November 15, the Australian Bureau of Statistics announced the result of the postal survey on same-sex marriage equality, a resounding Yes with 61.6% of the vote. Leading up to the announcement, the LBGTQIA+ community endured agonised tension. They had to argue fiercely for the legitimacy of their relationships as well as their identities.

During that debate a new visual landscape of signs and interventions became part of many urban environments. The rainbow pride flag began to appear at both public and private sites as a very visible sign of pride and affirmation.

In the past year the flag has clearly escaped the pole or the street bunting of pride festival times to become ever present. Post-plebiscite, we are reminded of the same-sex marriage vote, and that issues for queer people continue.

Read more: A year since the marriage equality vote, much has been gained – and there is still much to be done

Gilbert Baker originally designed the rainbow flag in 1979 for the San Francisco Pride Parade. Its purpose was to express the visibility and values of the gay and lesbian community. The flag’s colours represent healing, serenity, sex and nature.

Since then, the flag has undergone many remixes by different parts of the queer community to create further visibility for the diversity inherent in it.

Transgender woman and activist Monica Helms designed the transgender pride flag in 1999, retaining the stripe motif, but focusing on blue, pink and white to illustrate a spectrum of gender.

Monica Helms talks about designing the trans pride flag.A more recent design is the pansexual pride flag, designed by a Tumblr user known as Jasper in 2010. First disseminated on the site, it has become the most widely seen specific flag of the community, reused across the internet.

Read more: Explainer: what does it mean to be 'cisgender'?

What’s in a flag?

Cloth flags are significant cultural spatial markers. Affected by air, wind and light, static cloth is transformed in the slightest breeze, becoming alive and suggesting change as well as permanence.

The rainbow pride flag’s emphatic stripes activate a sense of colour and change, evoking new narratives and possibilities. The flag took on new cultural, social and political meaning as it moved from the air and onto homes and commercial premises.

Some flags, like one hung in the window of The Bank pub in Newtown, were emblazoned with YES in the centre. This left no questions about what the flag was supposed to represent – it was very specific about its contemporary political motivation.

An example of the flag leaving the fixed place of the pole is at 73 Liberty Street in Stanmore in Sydney’s inner west. Originally painted a shade of yellow beige, the house was transformed into a radiant spectrum of rainbow pride colours, with a black and white flag emblazoned with “Yes!” hung on the front. Visit it today and the colours remain as vibrant as ever.

73 Liberty Street in Stanmore.Tom Stoddard, Author provided

73 Liberty Street in Stanmore.Tom Stoddard, Author providedThe boldness of the flag’s colours radically alters the experience of moving past the generally bland facades of inner-city Sydney. We are now confronted by an eye-catching spectrum, the aesthetic energy of colour and space.

Bold colour, often spurned and even banned in some heritage suburbs such as Paddington, takes on a new uplifting vision. At stake is visibility. LGBTQIA+ communities do not appear and disappear at moments of political debates, but continue to actualise and make visible pride in their existence.

Read more: Coming out at work is not a one-off event

A politicised existence necessitates this, as the fight for equality is ongoing. The painted house is a visible urban marker that the queer community is here to stay.

So what is the significance of these persistent visual markers? On the one hand, their visual presence indicates the importance of a political debate undertaken more than one year ago.

More subtly it marks a cultural shift, where expression, be it personal or as a collective, affirms a community. Design and activism in these forms can become expressions of civic values, as space and place become the mouthpiece for cultural and social sentiments and statements.

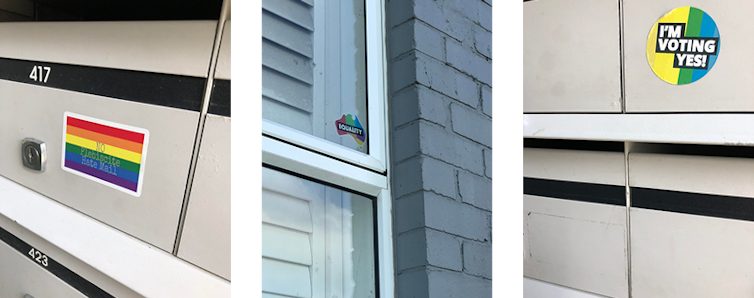

The flag leaves the pole: stickers around Marrickville, Sydney.Tom Stoddard, Author provided

The flag leaves the pole: stickers around Marrickville, Sydney.Tom Stoddard, Author providedThat isn’t to say that the static flag does not possess power in its own right. Various activist-designers have transformed it into other forms that create direct dialogues with the public. The rainbow flag stripes become a framing device for statements and declarations that are intrinsically tied to the language of the debate.

Stickers have long been used as spatially flexible political objects, free from flagpoles or other prerequisite structures. From letterboxes to window frames, remixed versions of the flag take a message or sentiment to any place, public or private.

This rethinking of the hierarchy of designated spaces for communication is an exciting evolution for the form and intention of the rainbow pride flag. As it evolves from one icon into a variety of others, it populates the city with queer statements and traces.

Last year the pride flag was used as an effective rallying call to express outwardly, publicly and explicitly that same-sex relationships (marriage or otherwise) are as valid as any heterosexual relationship. It will be interesting to see where the pride flag takes the Australian queer community next and, in turn, where the community takes the flag.

Tom Stoddard works for the University of Technology Sydney and receives funding and support for his research and writing.

Tom Lee works for the University of Technology Sydney and at times receives funding and support for his research and writing.

Authors: Thomas Stoddard, PhD Candidate, School of Design, University of Technology Sydney

| < Prev | Next > |

|---|