Black salve doesn't only destroy cancerous cells. from www.shutterstock.com

Black salve doesn't only destroy cancerous cells. from www.shutterstock.comYou might’ve heard the name black salve floating around in the media lately, accompanied by horror tales and even worse photos. But a quick google of the term will find just as many glowing reviews of miracle cancer cures.

Black salve is a product derived from the plant Sanguinaria canadensis, a perennial flowering plant native to northeastern America. It’s known colloquially as “blood root”, “Indian paint” and “red root”. The specific ingredients vary but commonly include zinc chloride (a destructive agent, which is corrosive to metals) as well as sanguinarine (a toxic plant extract).

Blood root was used by the American Indians, who harvested the plant from which they drained a red liquid. They thickened this into a paste, which they used to treat infected wounds. Early European settlers in America also used blood root to treat a variety of skin conditions including warts and moles.

Blood root is a strong escharotic, meaning it is a caustic and destructive material. The zinc chloride and sanguinare are corrosive, but dealers claim when it’s applied to damaged skin the healthy skin will separate and not be damaged. There’s no evidence to support this.

Instead, there’s evidence all tissue that comes into contact with the material is damaged, causing profound inflammation and eschar (a dry, dark scab or falling away of dead skin).

This can reasonably be compared to the result that would be expected from burning tissue by applying a strong caustic substance such as hydrochloric acid.

Its use in contemporary society dates back to the 1930s when researcher Fred Mohs used a preparation containing a low concentration of blood root to stabilise a tumour so he was able to examine it under a microscope.

This historical use has been used to give credibility to the use of black salve to treat skin malignancies, despite the fact Mohs publicly renounced its use for this purpose.

The salve doesn’t only destroy cancerous tissues, but all tissue.Flickr/Eli Christman, CC BY

The salve doesn’t only destroy cancerous tissues, but all tissue.Flickr/Eli Christman, CC BYRead more: Science or Snake Oil: can a detox actually cleanse your liver?

What is claimed about black salve’s benefits?

In the 1930s-50s Harry Hoxley, a self-proclaimed cancer specialist, sold salve to treat a variety of internal and external cancers in clinics in America. By the end of the 1950s, due to a lack of scientific evidence and concerns by medical authorities, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) had prohibited its sale.

One brand of black salve, Cansema (manufacturer Omega Alpha Labs), is marketed on the internet as:

a miraculous product with a miraculous history with roots that go back to the late 19th century.

The advertisement goes on to state:

Only suppression and greed have prevented its enormous benefits from being made available to the mainstream.

Many testimonials praising the results of Cansema are also listed on the internet. Within Australia, black salve has been marketed for the treatment of basal cell carcinoma (BCC), squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) and melanoma. Multiple websites provide testimonials supporting its use in this way and there are claims it’s not harmful to normal cells.

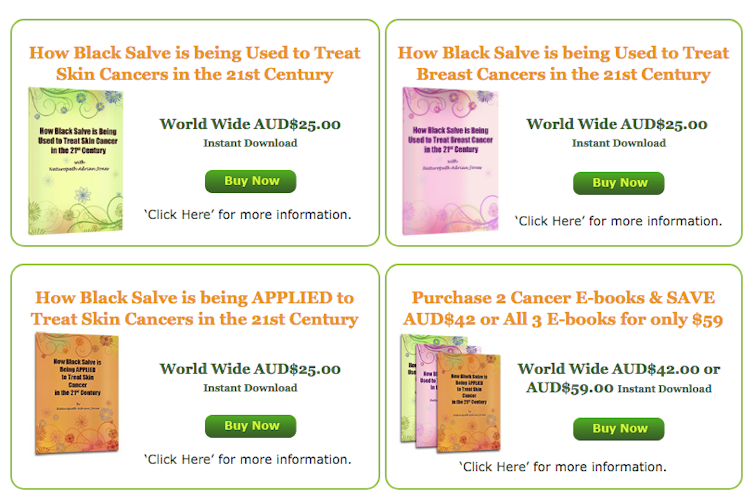

Cancer cures at bargain basement prices?Screenshot http://www.blacksalve.biz/

Cancer cures at bargain basement prices?Screenshot http://www.blacksalve.biz/Read more: Science or Snake Oil: do men need sperm health supplements?

Is there any evidence black salve cures cancer?

Salve appears under a variety of trade names including Cansema (Alpha Omega Labs), Black Ointment (Dr Christopher’s Original Formulas) and Herb Veil 8 (Altered States). No manufacturers have published detailed information about the specific ingredients.

There is, however, emerging laboratory evidence sanguinarine does have therapeutic anti-cancer effects. This evidence is based on studies on cells outside the body. These found beneficial effects, with selective destruction of malignant cells, but at much lower concentrations than in existing salve products. Higher concentrations result in destruction of normal tissue as well as cancer cells.

At the time of a recent review there were no studies comparing salve to conventional treatment so the safety and effectiveness remain unknown.

Read more: Science or Snake Oil: will horseradish and garlic really ease a cold?

Is black salve dangerous?

Documented adverse effects of black salve include direct damage to the skin, as well as disease progression where users eschew evidence-based therapy. In a recent review there were nine cases of biopsy-proven skin cancer treated with black salve and then documented.

All of these cases reported adverse clinical outcomes, including severe pain or discomfort, and seven reported significant adverse cosmetic outcomes. In six of these cases the cancer worsened. Two cases reported no worsening.

In one case colleagues and I reported there was progression to metastatic disease, meaning the cancer spread to lymph nodes and other organs, after seven years following treatment of a thin melanoma with black salve. The prognosis for 20-year survival of the primary melanoma at the time of black salve treatment was 97%. The patient died shortly after our manuscript was published.

In 2012 the Australian Therapeutic Goods Administration banned the sale of black salve in Australia due to a lack of evidence for its benefit. But it and its ingredients continue to be available for purchase through the internet and overseas.

In the future laboratory studies and ethical clinical trials might discover a beneficial role for blood-root products. But at present the use of black salve has no justifiable place in medical practice.

Read more: Science or Snake Oil: is A2 milk better for you than regular cow’s milk?

Associate Professor Cliff Rosendahl is affiliated with The University of Queensland where he is employed as a Course Coordinator in the UQ Skin Cancer Program. He is also a published author and as such receives royalties and payments from proceeds of sales. He also lectures on skin cancer subjects for multiple academic and private commercial organisations in various countries for which he from time to time receives payment with respect to travel costs, accommodation and honorariums.

Authors: Cliff Rosendahl, Associate Professor, The University of Queensland

| < Prev | Next > |

|---|