Standard serving sizes are anything but standard.Shutterstock

Standard serving sizes are anything but standard.ShutterstockThe Australian Guide to Healthy Eating sets out how much we should eat from each of the food groups. If we eat the recommended number of “standard serves” from each food group for our age and sex, it puts us in a good position to have a healthy, balanced diet.

But what is a standard serve? And does it match what’s on our food labels?

Standard serves

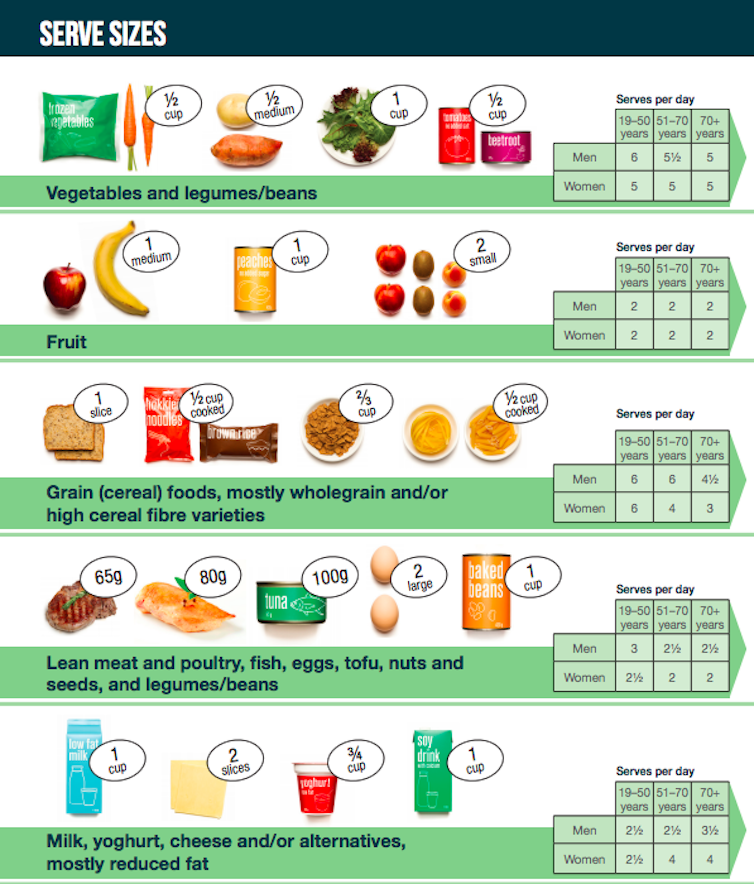

Despite the name, standard serves are not very standard, even in the Australian Guide to Healthy Eating. Serves can be described by energy (kilojoules or kJ for short) contained in a serve, units of food such as “one medium apple”, or “one slice of bread”, by weight, or by volumes like a cup.

Read more: Food as medicine: why do we need to eat so many vegetables and what does a serve actually look like?

A “serve” is also different between each of the food groups and even within the food groups.

One serve of grains is about 500kJ. That’s one English muffin but only half a bread roll. Or it could be half a cup of porridge, one-quarter of a cup of muesli, or three-quarters of a cup of wheat cereal flakes.

One serve of dairy is 500-600kJ, which could be one cup of milk, but is only three-quarters of a cup of yoghurt, or a half cup of ricotta cheese. Hard cheeses are defined by slices, with two slices to a serve, assuming each slice is about 20g.

Australia’s Guide to Healthy Eating outlines the number of serves we need each day to stay healthy.eatforhealth.gov.au

Australia’s Guide to Healthy Eating outlines the number of serves we need each day to stay healthy.eatforhealth.gov.auServes on food labels

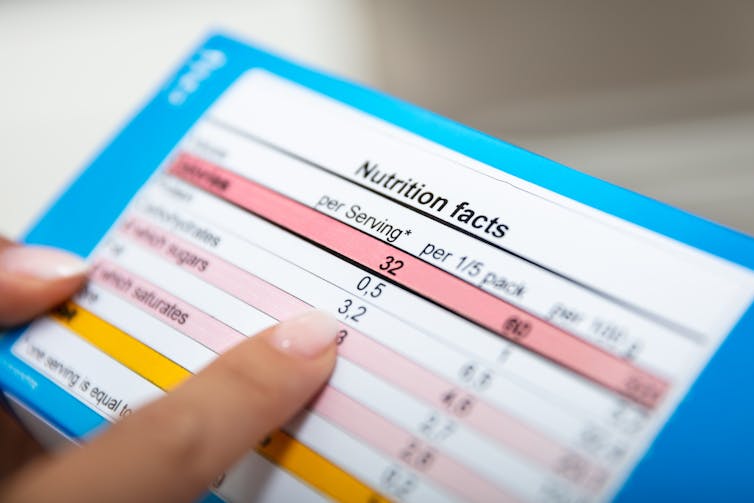

Nearly all packaged foods in Australia have nutrition information panels. These include information meant to help us make better food choices.

The exact information depends on the food. But they have to at least include how much energy (kJ), protein, fat (total and saturated), carbohydrates (total and sugars) and salt (sodium) is in the product. These contents are always listed twice, per 100g (100mL for liquids) and per serving.

The manufacturer sets the food label’s serving size.Andrey_Popov/Shutterstock

The manufacturer sets the food label’s serving size.Andrey_Popov/ShutterstockBut the serving on the label has nothing to do with the standard serves in the Australian Guide to Healthy Eating. The serving size on the label is not a recommendation on how much you should eat – it is decided by the manufacturer. It’s based on how much they expect a person to typically eat, or the unit size the product is eaten in.

This could be very different to a standard serve. For example, the labelled serving size on a chocolate bar might be “one bar” – 53g of chocolate containing 1,020kJ. But the Australian Guide to Healthy Eating says a serve is half a small bar (25g) or about 600kJ, and it’s recommended we limit discretionary food (junk food) to one serve per day.

Comparing serving sizes between brand and package sizes

In Australia, there are no rules about how these serving sizes are set. A serving might not be the same in similar products, or in different brands of the same product.

This can make products hard to compare. The serving size of a soy sauce in one brand, for example, could be one-tenth of a soy sauce made by another company.

Read more: Fat free and 100% natural: seven food labelling tricks exposed

To add to the confusion, a serving also doesn’t necessarily reflect portion size: how much a person consumes in a meal or sitting.

A 250g packet of microwave white rice, for example, might be labelled as having two 125g servings. This is because the manufacturer expects it to serve two people. But one of those labelled servings is almost two standard serves of grains.

To make it even more confusing, in the same brand of rice, a 450g family pack could be labelled as having four serves, with each serve 112g. That’s 10% smaller than the serving size in the smaller packet. But it assumes a family of four could split the pack between them in a meal. So, in this package, one labelled serving size would be the equivalent of about 1.7 standard serves of grains.

How serves on labels impact our food choices

Even though labelled serving sizes are not related to standard serves or the recommended amounts that should be eaten, research shows consumers often interpret the labelled servings as being recommendations for portion size or for following dietary guidelines.

Studies show the listed serving size impacts how much people choose to eat. Larger serving sizes on labels can make it appear that a large serve is recommended, leading to people eating or serving themselves more. This has been shown with several foods, including cookies, cereal, lasagne and cheese crackers.

A larger serving size on the lasagne label might mean you’re likely to eat more of it.Stockcreations/shutterstock

A larger serving size on the lasagne label might mean you’re likely to eat more of it.Stockcreations/shutterstockBut for some foods, like lollies, larger serving sizes can make them look less healthy, leading to reduced consumption or smaller portion sizes. This is likely because the large number of kilojoules stands out in the per serving data.

So what should you do?

Because serving sizes can vary by product and manufacturer, it’s easiest to use the per 100g or 100mL information, instead of the per serve information when comparing products. But think about the actual weight or volume you will consumer when you consider how it fits your daily intakes.

The recommended diet for the average adult is based on eating 8,700kJ of energy per day. To get this much energy from a balanced diet, that’s 50g protein, 70g fat and 310g carbohydrates. We also want to aim for 24g or less of saturated fats, and 30g or more of fibre.

But needs will differ by life stage, activity level, sex, your current weight and your weight goals. There are online calculators to estimate your requirements.

Memorising serving sizes and guidelines can be hard. To make it easy, you can print a copy of the Australian Guide to Healthy Eating food groups and serving sizes to keep where you can see them when preparing food.

Read more: Health Check: how to work out how much food you should eat

Emma Beckett receives funding from the National Health and Medical Research Council and the AMP Foundation. She has consulted for Kelloggs Australia. She is a member of the Nutrition Society of Australia, the Australian Institute of Food Science and Technology and the Early and Mid Career Researcher Forum Executive.

Tamara Bucher has received research funding from government and non-government organisations and industry. Funding sources include the Swiss National Science Foundation, the Swiss Foundation for Nutrition Research, the European Commission, the Swiss Academy of Humanities and Social Sciences, the Walter Hochstrasser Stiftung, Nestlé S.A., SafeFood UK, Goodman Fielder and Rijk Zwaan Australia. She is a member of the Nutrition Society of Australia and the International Society for Behavioural Nutrition and Physical Activity.

Authors: Emma Beckett, Lecturer (Food Science and Human Nutrition), School of Environmental and Life Sciences, University of Newcastle

| < Prev | Next > |

|---|